Rosenwein explores how anger has been characterized by gender and race, why it has been tied to violence and how that is often a false connection, how it has figured among the seven deadly sins and yet is considered a virtue, and how its interpretation, once largely the preserve of philosophers and theologians, has been gradually handed over to scientists—with very mixed results.

Book Details

Author: Barbara H. Rosenwein is professor emerita at Loyola University Chicago. She is the author of numerous books, including Anger’s Past: The Social Uses of an Emotion in the Middle Ages and Generations of Feeling: A History of Emotions, 600–1700.

Publisher: Yale University Press (July 14, 2020)

Language: English

Hardcover: 224 pages

ISBN-10: 0300221428

ISBN-13: 978-0300221428

Item Weight: 1.15 pounds

Dimensions: 5.7 x 1.1 x 8.6 inches

The title of Barbara Rosenwein’s recent book is misleading: Anger (singular): The conflicted history of an emotion (singular). The title suggests that the book treats “anger” as a singular entity, an emotion or concept with a universal common denominator, whose evolution and contested meanings could be traced from antiquity to the present.[1] This is not the case.

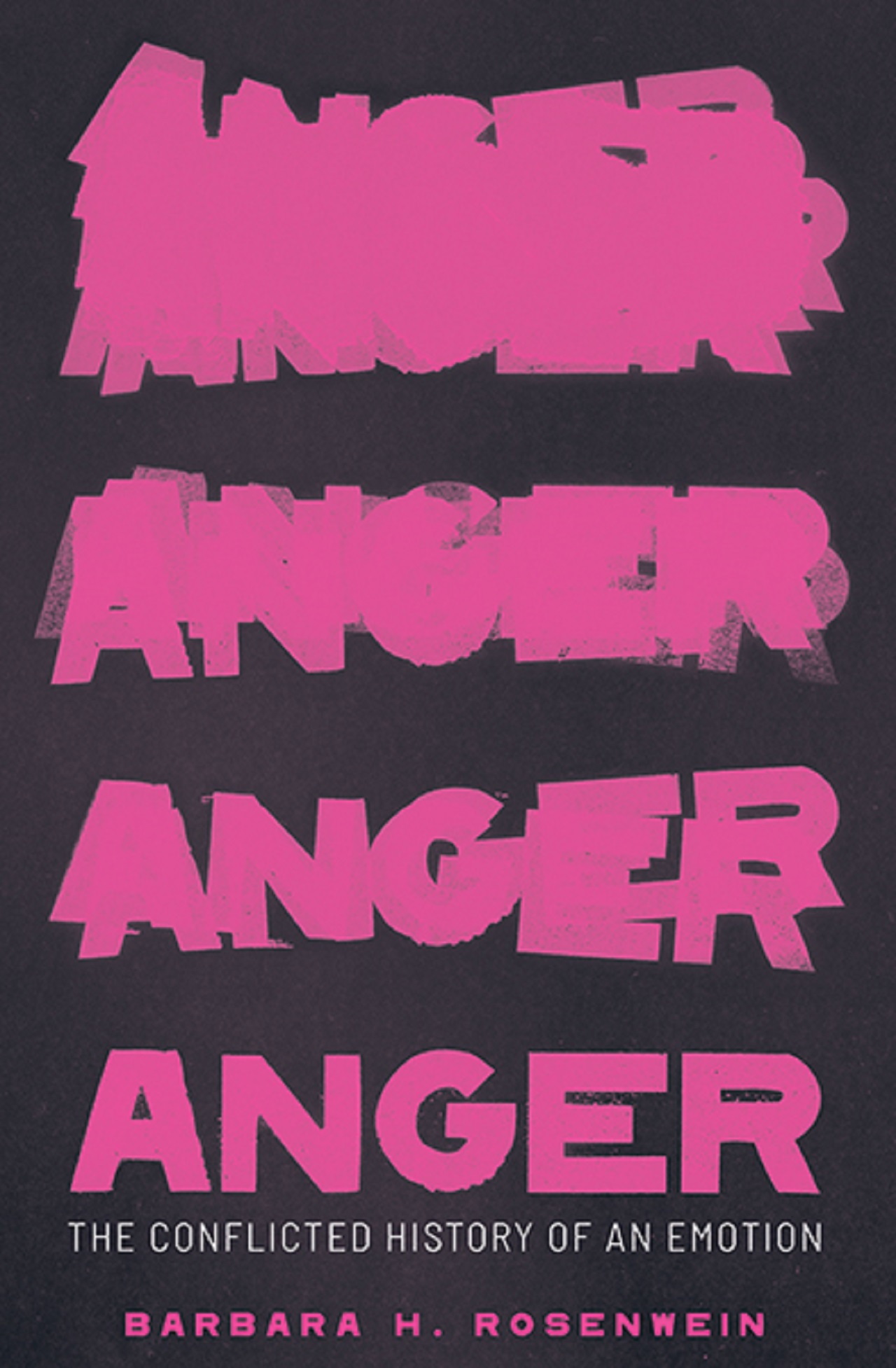

The cover design, by Alex Kirby, comes closer to describing the content of the book and Barbara Rosenwein’s approach to anger. The word anger is printed in four pink blocks against a dark background. At the bottom, the bold, capital letters of the word appear clear. In the blocks above, the word has been stamped multiple times with different angles – twice into the second block up, thrice into the third and apparently four of five times into the highest block, making the word almost unreadable. In this design, anger appears multiple, layered, blurred and ambiguous. The closer the word anger is to the author’s name on the cover, the clearer it appears. The more distant the word or concept is from the author, the blurrier and the more ambiguous it gets, finally appearing unidentifiable.

One could interpret this design to represent stages in research. Does the researcher start with a blurry image that becomes clearer step by step, or does the researcher start with a clear concept of anger, that appears more layered and ambiguous the further she conducts her research? Both are true.

Barbara Rosenwein invites us, her readers, to look at and “rejoice … about that larger picture” (p. 200) of the many angers in history and the present, however ambiguous, blurred or distant they appear initially. The more we learn about the diversity of words, narratives, scripts, moral judgements, bodily enactments, medical practices and religious beliefs about anger, “the better we will be able to navigate our own lives” (p. 199). If the starting point and aim of any history of emotions is the understanding of one’s own feelings, and the emotions that govern one’s own emotional communities, it is logical that the English word “anger” features on the cover and that Rosenwein starts to explore angers in histories by placing a personal experience and memory at the centre of her larger picture. When she was a child, she tells us, she would sometimes beat her favourite doll. Her mother would explain the behaviour to a visitor with the words “That girl has a lot of anger in her”. Rosenwein asks: “What was this anger that I had a lot of?” (pp. 1-2).

The book – an extended historical answer to Rosenwein’s question – explores anger in three parts. The first is entitled, “Anger rejected (almost) absolutely” (pp. 10-79), and explores traditions of thought which follow the imperatives “abandon anger” and “avoid anger” – from Buddhist writings to contemporary anger management strategies for managers; from Seneca and the Stoics to the contemporary Neo-Stoics, such as Martha Nussbaum’s plea ‘avoid anger, embrace forgiveness and give peace a chance’[2]; from biblical ideas of peaceable kingdoms to contemporary violence in the name of religion.

Exploring the relations between anger and violence is a motif which runs throughout all the subchapters of part one. Rosenwein notes that “in the modern Western mind, anger, violence, and aggression are persistently associated, almost a ‘knee-jerk reaction’” (p. 65). She wants to break this assumption by showing that “peace is not the opposite of anger, and violence is not necessarily anger’s outcome” (p. 66). The stressing of this argument can be understood as a critique of Pankaj Mishra’s widely read 2017 book, Age of Anger.[3] Mishra traces conflict and political violence almost exclusively back to a universal kind of anger, which accumulated as a reaction to injustices brought about by the colonialist infliction of Western modernity on the world as a whole. Rosenwein argues:

Some of us worry that our many angers – so profoundly delightful, horrible, frightening, and powerful – will tear apart our social fabric. But in part that is because we have simplified a very complicated matter by labelling so many different feelings and behaviours “angry”. This book teases out the particulars and, by doing so, aims to give us a new perspective on ourselves and our era. (p. 7)

The first part concludes with a reflection on the performative power of angry words and words for anger, which brings us back to the centre of Rosenwein’s anger picture – her own childhood memory. If she assumed that her mother’s naming of the behaviour was a transformative speech act, which made little Barbara’s behaviour anger by naming it as such, the concept was still open to interpretation: “Buddha would have agreed that my anger was … wrong-headed and self-destructive” (p. 10). From a Stoic point of view, the beating of the doll could have been an incident of anger as proper judgement and reasoned punishment – “perhaps in my mind, my doll had done something bad” (p. 39). In the Aristotelian view and its modern adaptations, the child had maybe acted out or mirrored the vengeful anger of her father, who talked at home about how he felt treated unjustly on his job (p. 83). Not only are there multiple angers, even one anger concept has multiple and often conflicted meanings. Why do we name and label feelings and behaviours the way we do? And what have goal orientation and morality to do with it?

This is the starting point for the second part of the book on “Anger as a vice but also (sometimes) as a virtue” (pp. 82-128). This part explores moral evaluations of anger and how anger was used to explain, condemn, excuse, justify or motivate aggressive behaviours. It also reflects a history of thought on the relation of body and mind, reason and emotion, in philosophical, religious and scholarly writing. The larger picture of anger is held together by constantly connecting contemporary angers to those of the past. For example, when Rosenwein explains that the Medieval Christian notion of “anger as righteous, passionate, virtuous and productive would have a potent future in the modern world” (p. 113) – which is another moment of countering Mishra’s historiography of anger – while she notices that there runs a parallel development of a declining acceptance of anger in America, as has been described by Peter and Carol Stearns in their book on anger from 1986.[4]

The conclusion of part two is one of the rare instances where Rosenwein allows herself to cast moral judgement on an anger. She writes:

the problem is the very idea of righteous anger. Our voices would be far less discordant if we did not believe that our anger is just and virtuous while ‘theirs’ is not, if we admitted that we might possibly be wrong (p. 128).

Emotional pluralism, the acknowledgement that different emotional communities have different angers with shared and distinct and conflicted histories, is at the core of her methodology and the moral standpoint expressed with most clarity in part two.

The third part, titled “Natural anger”, discusses the idea of anger as a natural phenomenon or natural force that affects the human body and mind or is produced by them. It presents anger as a subject in the medical and natural sciences, starting with Galen in antiquity and ending with neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett in the present. The question that dominates the research discourse in the 20th and 21st centuries is to what extend anger is shaped by nature (genes, evolution, basic instincts, bodily reactions) and to what extend is shaped by culture and society (learning and conceptualizing emotions). Rosenwein makes clear that these debates are not only of interest with regard to research, but also because political angers tend to get explained as either natural und thus unstoppable forces, or as social constructs that could be managed, avoided or abandoned, if people only wanted to. Rosenwein concludes that the “key challenge for today’s celebration of so many angers is to step back from the flash point of their combustible explosivity and begin to talk” about the goals and aims that motivate them (p. 195).

What I personally like about Barbara Rosenwein’s book is that she does not claim to have found the new key to solving anger as a problem – in fact, she does not even claim that anger necessarily is a problem. Unlike other authors of recent anger books that gained popularity, Rosenwein keeps the moral impetus low. To put it in a simplified (and maybe slightly unfair) way: Pankaj Mishra is countering anger with anger (fighting fire with fire). Martha Nussbaum suggests we can simply answer anger with forgiveness (fighting fire with a smile). Barbara Rosenwein promotes pluralism and suggests that we should all develop an empathetic understanding for the many angers, past and present, before we judge and act (approaching fire with fireology).

I am usually a fan of academic activism and the idea of translating knowledge into action in the spirit of wanting to improve the world. But since anger concepts are very much linked to violence and power in present day emotionologies, not only in meta-discourse but in the politics of action, where angers are used as tools of mobilization (p. 191)[5], I read Barbara Rosenwein’s book as an invitation to move the intellectual discourse and activism on anger beyond the one-moral-judgement-fits-all approach.

In Rosenwein’s book anger is a vice and a virtue, violent and calm behaviour, the reaction to injustice and a child’s play. Anger is felt as uncomfortable and pleasurable, in the brain, in the heart, in the pulse and without measurable bodily alterations. Anger has been identified and misinterpreted in faces, has been named with agreement and disagreement. Which brings us back to the fundamental question, that Thomas Dixon asked in the title of his recent article: “What is the history of anger a history of?”[6]

Anger. The conflicted history of an emotion is a history of knowledge traditions which Barbara Rosenwein chose as ‘having to do with anger’ on the basis of her own memories, experiences, knowledge and observations. The strength of her approach is the transparency of why and how she chose the topics and examples for her book. She addresses the blind spots and gaps in her larger picture of the angers in histories. At the same time, she expresses the desire to see more and fill those gaps. Is this approach an excuse for writing Eurocentric history, or a way of acknowledging pluralism while actually dismissing it? It could be. But it could also be understood as a call for building collective knowledge on the many angers in the field of the history of emotion, because one book will never be able to do justice to the topic.

The beauty and challenge of pluralism is, that there are multiple and often conflicting answers to one question. Therefore we should take notice of the cover and its message about how a history of anger – or any emotion – appears more ambiguous, layered and maybe even incomplete, the more you discover about it.

About the Author

I am a medievalist by training and now a historian of emotions as well. Professor emerita at Loyola University Chicago, I am the author most recently of “Anger: The Conflicted History of an Emotion,” (Yale, 2020); “Emotional Communities in the Early Middle Ages” (Cornell, 2006); “Generations of Feeling: A History of Emotions, 600-1700” (CUP, 2015), translated into Italian as “Generazioni di sentimenti. Una storia delle emozioni, 600-1700,” trans. and ed. Riccardo Cristiani (Viella, 2016); (with Riccardo Cristiani), “What is the History of Emotions?” (Polity Press, 2018); and (with Elina Gertsman), “The Middle Ages in 50 Objects” (Cambridge, 2018). My textbooks include “A Short History of the Middle Ages,” currently in its 5th ed. (U. of Toronto Press, 2018), “Reading the Middle Ages: Sources from Europe, Byzantium, and the Islamic World,” currently in its 3d ed. (U. of Toronto Press, 2018), and (with L. Hunt, T. R. Martin and B. G. Smith), “The Making of the West: Peoples and Cultures,” soon to be published in its 7th ed. (Bedford/St. Martin’s).

I am a medievalist by training and now a historian of emotions as well. Professor emerita at Loyola University Chicago, I am the author most recently of “Anger: The Conflicted History of an Emotion,” (Yale, 2020); “Emotional Communities in the Early Middle Ages” (Cornell, 2006); “Generations of Feeling: A History of Emotions, 600-1700” (CUP, 2015), translated into Italian as “Generazioni di sentimenti. Una storia delle emozioni, 600-1700,” trans. and ed. Riccardo Cristiani (Viella, 2016); (with Riccardo Cristiani), “What is the History of Emotions?” (Polity Press, 2018); and (with Elina Gertsman), “The Middle Ages in 50 Objects” (Cambridge, 2018). My textbooks include “A Short History of the Middle Ages,” currently in its 5th ed. (U. of Toronto Press, 2018), “Reading the Middle Ages: Sources from Europe, Byzantium, and the Islamic World,” currently in its 3d ed. (U. of Toronto Press, 2018), and (with L. Hunt, T. R. Martin and B. G. Smith), “The Making of the West: Peoples and Cultures,” soon to be published in its 7th ed. (Bedford/St. Martin’s).

References

[1] The criticism on anger in the singular has also been made in greater detail and depths by Thomas Dixon in his recent article from 2020: What is the History of Anger a History of? Emotions: History, Culture, Society 4, 1-34, p. 28.

[2] Martha Nussbaum (2016). Anger and Forgiveness: Resentment, Generosity and Justice, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[3] Pankaj Mishra (2017). Age of Anger: A History of the Present, New York: Picador.

[4] Carol Stearns and Peter Stearns (1986): Anger: The Struggle for Emotional Control in America’s History, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[5] See for example Amélie Blom and Stephanie Tawa Lama-Rewal, Eds (2020). Emotions, Mobilisations and South Asian Politics, London, New York: Routledge.

[6] Thomas Dixon, ‘What is the history of anger a history of’, Emotions: History, Culture, Society 4.1 (2020): 1-34.