Punishment for cheating and bribery in the Olympics of Ancient Greece could include fines, public flogging and statewide bans from competition

Ancient Olympians didn’t have performance-enhancing drugs at their disposal, but according to those who know the era best, if the ancient Greeks could have doped, a number of athletes definitely would have. “We only know of a small number of examples of cheating but it was probably fairly common,” says David Gilman Romano, a professor of Greek archaeology at the University of Arizona. And yet the athletes had competing interests. “Law, oaths, rules, vigilant officials, tradition, the fear of flogging, the religious setting of the games, a personal sense of honor – all these contributed to keep Greek athletic contests clean,” wrote Clarence A. Forbes, a professor of Classics at Ohio State University, in 1952. “And most of the thousands of contests over the centuries were clean.”

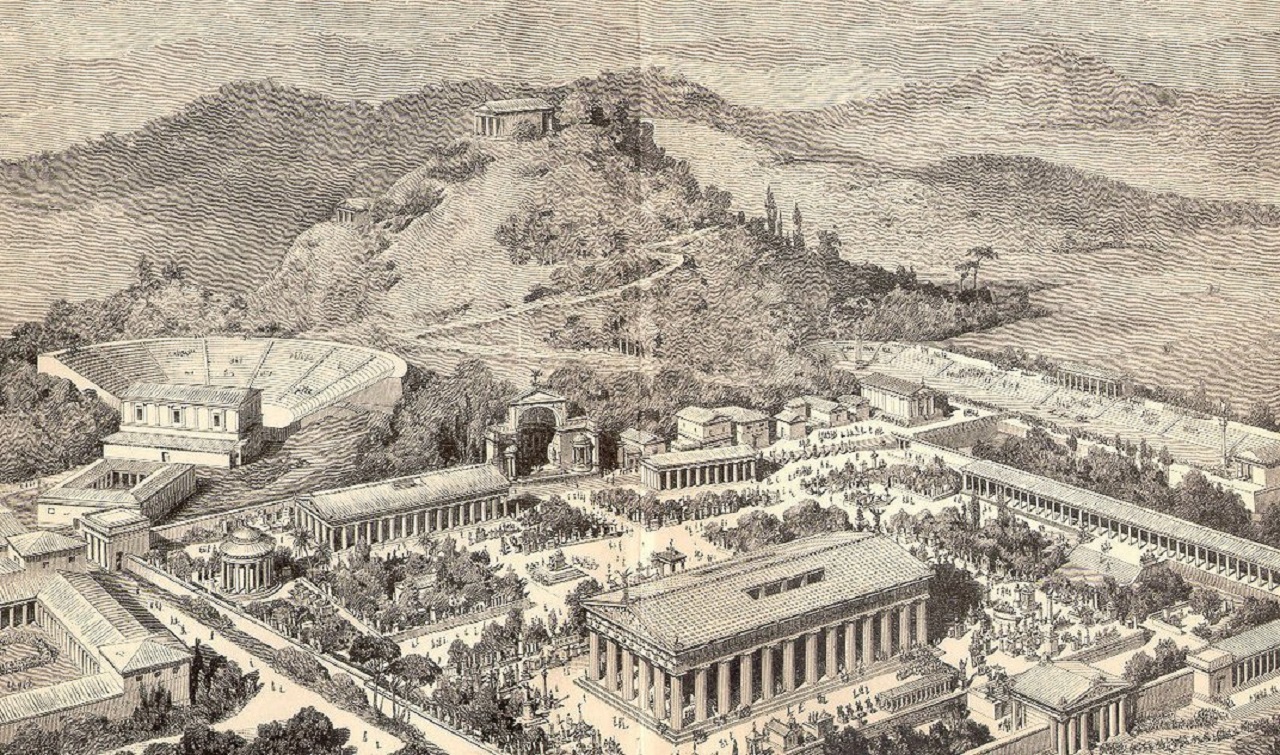

Judging from the writings of the second-century A.D. traveler named Pausanias, however, most cheating in the ancient Olympics was related to bribery or foul play. Not coincidentally, the mythological basis of the Olympic games involves both, according to Romano’s writing. The figure thought to have founded the Olympic Games, Pelops, did so as a celebration of his marriage and chariot victory over the wealthy king Oinomaos, spoils he only gained after bribing the king’s charioteer to sabotage the royal’s ride. The first Games are said to have been held in 776 B.C., though archeological evidence suggest they may have begun centuries earlier.

Cheating seems to have been rare at the ancient Olympics, which traditionally started in 776 B.C. and were held every 4 years thereafter. It is assumed there were cheaters in addition to the known ones listed below, but the judges, Hellanodikai, were considered honest, and on the whole, so were the athletes—partly deterred by stiff fines and the possibility of flogging.

This list is based on zane-statue witness Pausanias but comes directly from the following article: “Crime and Punishment in Greek Athletics,” by Clarence A. Forbes. The Classical Journal, Vol. 47, No. 5, (Feb., 1952), pp. 169-203.

Gelo of Syracuse

Gelo of Gela won an Olympic victory, in 488, for the chariot. Astylus of Croton won in the stade and diaulos races. When Gelo became tyrant of Syracuse — as happened more than once to the much adored and honored Olympic victors — in 485, he persuaded Astylus to run for his city. Bribery is assumed. The angry people of Croton tore down Astylus’ Olympic statue and seized his house.

Lichas of Sparta

In 420, the Spartans were excluded from participation, but a Spartan named Lichas entered his chariot horses as Thebans. When the team won, Lichas ran onto the field. The Hellanodikai sent attendants to flog him as punishment.

“Arcesilaus won two Olympic victories. His son Lichas, because at that time the Lacedaemonians were excluded from the games, entered his chariot in the name of the Theban people; and when his chariot won, Lichas with his own hands tied a ribbon on the charioteer: for this he was whipped by the umpires.”

Pausanias Book VI.2

Eupolus of Thessaly

During the 98th Olympics, in 388 B.C. a boxer named Eupolus bribed his 3 opponents to let him win. The Hellanodikai fined all four men. The fines paid for a row of bronze statues of Zeus with inscriptions explaining what had happened. These 6 bronze statues were the first of the zanes.

The Romans used the system of damnatio memoriae to purge the memory of despised men. Egyptians did something similar [see Hatshepsut], but the Greeks did virtually the opposite, memorializing the names of miscreants so their example couldn’t be forgotten.

“2 2. On the way from the Metroum to the stadium there is on the left, at the foot of Mount Cronius, a terrace of stone close to the mountain, and steps lead up through the terrace. At the terrace stand bronze images of Zeus. These images were made from the fines imposed on athletes who wantonly violated the rules of the games: they are called Zanes (Zeuses) by the natives. At first six were set up in the ninety-eighth Olympiad; for Eupolus, a Thessalian, bribed the boxers who presented themselves, to wit, Agetor, an Arcadian, Prytanis of Cyzicus, and Phormio of Halicarnassus, the last of whom had been victorious in the preceding Olympiad They say that this was the first offence committed by athletes against the rules of the games, and Eupolus and the men he bribed were the first who were fined by the Eleans. Two of the images are by Cleon of Sicyon: I do not know who made the next four. These images, with the exception of the third and fourth, bear inscriptions in elegiac verse. The purport of the verses on the first is that an Olympic victory is to be gained, not by money, but by fleetness of foot and strength of body. The verses on the second declare that the image has been set up in honour of the deity and by the piety of the Eleans, and to be a terror to athletes who transgress. The sense of the inscription on the fifth image is a general praise of the Eleans, with a particular reference to the punishment of the boxers; and on the sixth and last it is stated that the images are a warning to all the Greeks not to give money for the purpose of gaining an Olympic victory.”

Pausanias V

Dionysius of Syracuse

When Dionysius became tyrant of Syracuse, he tried to persuade the father of Antipater, the boys’ class winning boxer, to claim his city as Syracuse. Antipater’s Milesian father refused. Dionysius had more success claiming a later Olympic victory in 384 (99th Olympics). Dicon of Caulonia legitimately claimed Syracuse as his city when he won the stade race. It was legitimate because Dionysius had conquered Caulonia.

Ephesus and Sotades of Crete

In the 100th Olympics, Ephesus bribed a Cretan athlete, Sotades, to claim Ephesus as his city when he won the long race. Sotades was exiled by Crete.

“4. Sotades won the long race in the ninety-ninth Olympiad, and was proclaimed as a Cretan, as in fact he was; but in the next Olympiad he was bribed by the Ephesian community to accept the citizenship of Ephesus. For this he was punished with exile by the Cretans.”

Pausanias Book VI.18

The Hellanodikai

The Hellanodikai were considered honest, but there were exceptions. They were required to be citizens of Elis and in 396, when they judged a stade race, two of the three voted for Eupolemus of Elis, while the other voted for Leon of Ambracia. When Leon appealed the decision to the Olympic Council, the two partisan Hellanodikai were fined, but Eupolemus maintained the victory.

There were other officials who may have been corrupt. Plutarch suggests umpires (brabeutai) sometimes awarded crowns incorrectly.

“The statue of Eupolemus, an Elean, is by Daedalus, of Sicyon the inscription on it sets forth that Eupolemus was victor at Olympia in the men’s foot-race, and that he also won two Pythian crowns in the pentathlum, and one at Nemea. It is said about Eupolemus that three umpires were appointed to judge the race, and that two of them gave the victory to Eupolemus, but one of them to Leon, an Ambraciot, and that Leon got the Olympic Council to fine both the judges who had decided in favour of Eupolemus.”

Pausanias Book VI.2

Callippus of Athens

In 332 B.C., during the 112th Olympics, Callipus of Athens, a pentathlete, bribed his competitors. Again, the Hellanodikai found out and fined all offenders. Athens sent an orator to try to persuade Elis to remit the fine. Unsuccessful, the Athenians refused to pay and withdrew from the Olympics. It took the Delphic Oracle to persuade Athens to pay. A second group of 6 bronze zane statues of Zeus was erected from the fines.

Eudelus and Philostratus of Rhodes

In 68 B.C., during the 178th Olympics, Eudelus paid a Rhodian to let him win a preliminary wrestling competition. Found out, both men and the city of Rhodes paid a fine, and so there were two more zane statues.

Fathers of Polyctor of Elis and Sosander of Smyrna

In 12 B.C. two more zanes were built at the expense of fathers of wrestlers from Elis and Smyrna.

Didas and Sarapammon From the Arsinoite Nome

Boxers from Egypt paid for zanes built in A.D. 125.

“Cheating has always been part of sports,” Maurice Schweitzer, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania who researches deception, told me. “It’s this idea that we’re ‘in it to win it,’ and we will cut corners or push ourselves really hard, so the Little League World Series has scandals, the Paralympics has scandals.”

Cheating, it seems from recent research, creates its own ecosystem, because winners are more likely to cheat, cheaters are more likely to win, and emotions tied to winning—feelings of superiority, or that you deserve to excel—reinforce cheating behavior. Schweitzer’s work has found cheaters experience a sort of double high: the high of having won, and a high from having duped everyone.

This year, with news officials let Russian figure skater Kamila Valieva compete even though she had tested positive for a banned substance, it seems cheating has progressed to a height never before achieved—at least since the Cold War when Eastern Bloc athletes were accused of using drugs to boost their performances. And because cheating has been so deeply involved in the Olympics since its creation, it’s in keeping with the Olympic motto of pushing limits: Citius, Altius, Fortius. Faster, Higher, Stronger.

References

Gill, N.S. “Cheating During the Ancient Olympics.” ThoughtCo, Aug. 26, 2020, thoughtco.com/cheating-during-the-ancient-olympics-120134.

Shavin, N. “The Ancient History of Cheating in the Olympics” smithsonianmag.com