No diploma and no graduation, that was the punishment. Five students had organized a large public protest on their university campus. A scholar who opposed the #blacklivesmatter movement had come to their school to deliver a public lecture. In response, the students formed a blockade in front of the venue disrupting the speaker’s event. A violation of school policy, the administration laid down the law and widened the gulf of mistrust between the students and the university. The student newspaper quickly published a series of critical editorials and students railed against the administration on social media. One year later, prepared or not, I arrived on campus to serve as a student chaplain.

In today’s tense cultural climate universities are attempting to balance two important academic commitments as they serve and educate students. On the one hand, student affairs staff are working hard to welcome, retain, and help students of color so that the larger learning community can benefit from their presence and participation. These students possess valuable abilities and insights, they also offer diverse cultural wealth that enriches academic discourse. The wealth of their insight is often forged in the fires of marginalization and resistance to cultural and racial oppression.

On the other hand, some university leaders are committed to protecting a free dialogical space for open debate and disagreement. These leaders work hard to welcome dissenting voices onto campus who do not accede to all of the doctrines of Critical Race Theory (CRT). These dissenting voices may define key terms, like “racism,” very differently. As the struggle to set the terms of the conversation goes on, the failure to agree on definitions and boundaries leads to accusations of libel and even injury. To be labeled a “racist” or a “snowflake” only deepens distrust and inhibits dialogue. University leaders who work to keep dialogical spaces open are condemned. From one side they are attacked for normalizing “political correctness” (another imprecisely utilized and weaponized term). From the other side they are dignifying a social imaginary circumscribed by racism. These dynamics play out at almost every kind of campus on which I have worked or spoken.

Navigating these campus conflicts as a Christian theologian and an East Asian American male is an ongoing challenge for me. I have served in university ministry for almost twenty years, and I have long been puzzled by the ubiquity of students who deny that racism is, in fact, the ordinary experience for many people of color.[1] The denial of this reality for Asian Americans by Asian Americans is all the more perplexing to me. That some university communities do not consider Asian Americans “people of color” both creates and reinforces this self-marginalization.[2] I have struggled with the black-white nature of race dialogue in the United States, the way this binary positions Asian American Studies, and the havoc it creates for the formation of Asian American students.

Christians on campus today regularly encounter the complex language, presuppositions, and values of Critical Race Theory. Christians who engage in CRT’s critical questioning of power dynamics across race may learn to clearly assess inequities and unfairnesses that forestall meaningful relationships across race. However, these Christians may—for that very reason—face greater challenges to building trusting relationships with those whom they critique as participating in and/or benefitting from inequitable systems. To aver that, “racism is ordinary,” is to say that people of color have not been caught off guard or surprised when racist atrocities are reported. These reports of oppression are not a scandalizing aberration from the norms of polite society—they’re ordinary. Yet, this assertion—perhaps the most self-evident of the core tenets of CRT to college students—puts critical students at odds with those who behold American culture more adoringly.

Scholarship on Christianity and Critical Race Theory is beginning to pick up speed.[3] Some Christian individuals and institutions reject CRT out of hand while others embrace it without question. This essay seeks to resource those for whom a distinctively Christian vision of racial justice is desired—a vision that takes the pain of oppressed communities, the Reformed confessions, and the rapidly evolving conversation on race seriously.

Sketching Critical Race Theory

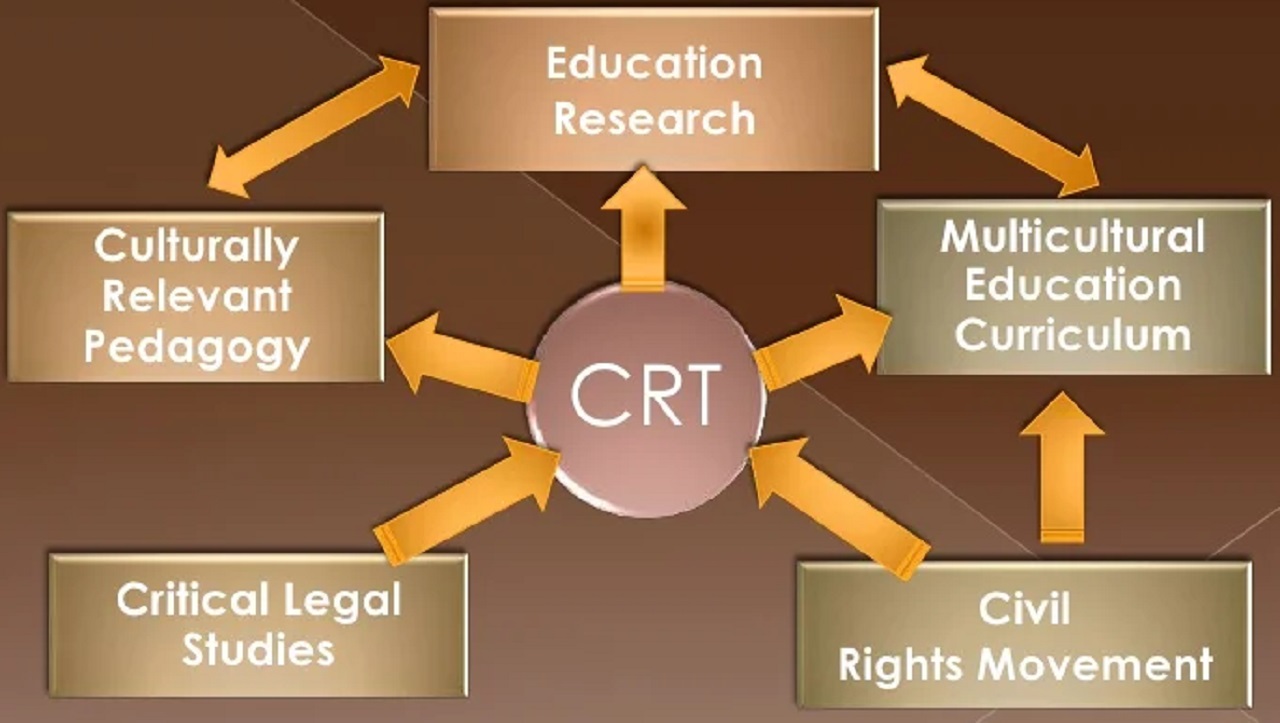

While its enduring impact is undeniable, the Civil Rights Movement in America has been criticized for not going far enough. The movement fundamentally lacked the critical tools necessary to fully understand and address the depth, breadth, and interconnected nature of racism, sexism, and classism within Western culture and its institutions. Critical Race Theory arose in the 1970s and 1980s to fill this gap when a group of scholar-activists independently arrived at this very conclusion.

CRT began in legal studies, focusing on racial inequalities within the American justice system. Racial inequality, CRT argued, is embedded within the complex systems and interconnected structures of society. In other words, “racism” is deeper and more pervasive than isolated instances of racial strife between individuals. This inequality is reflected in and reinforced by the legal code itself which, despite Civil Rights gains, was not so significantly altered as to prevent racial injustice from proliferating.

Since its genesis in the mid-1970s, the critical tools of CRT have been employed in a wide range of academic fields, including but not limited to educational, literary, historical, public policy, and now theological studies.[4] Foundational Western assumptions, canons, and methods in these fields—previously unquestioned—are now under tremendous critical scrutiny. The errors of racialized reasoning along with the disproportionate influence of whiteness are now a frequent target for academic critique.[5]

The demand for universities to expand their academic considerations beyond whiteness is already challenging. CRT’s philosophical reliance on the critical tools of the Marxist, Frankfurt school causes even more discomfort. The Frankfurt school provides CRT with the conceptual tools to understand the ways in which societal systems and structures can effectively reproduce patterns of inequality.

Let’s take, for example, liberal individualism and its promise of a meritocratic society. For decades Wall Street and Hollywood Blvd have projected the false promise that, if they work hard, people of color can succeed economically, politically, and culturally in this purely meritocratic society. Through individual effort they can rise through the institutions of western culture and self-actualize. Critical Race Theory seeks to dismantle the myth of meritocracy and expose the multiplicity of ways in which formal and informal societal systems and patterns within the West raise some identities up and push other identities down.

There are a number of tenets that are particularly foundational for CRT. That the experience of racism is ordinary, systemic, and cultural, (as opposed to isolated, individualistic, and intellectual) is both first and foundational to CRT. A second pillar is that of “interest convergence.” Studying the limited successes of the civil rights movement, CRT scholars found that legislative victories for civil rights coincided “with the dictates of white self-interest. Little happens out of altruism alone.”[6] Systems and structures of oppression only change when it is in their clear self-interest to do so. Third, CRT seeks to expose and deconstruct false claims of colorblindness and neutrality in scholarship, society, and politics. CRT argues that abstract rationalistic claims of unbiased universality are an impracticable myth. Every scholar and every public leader bring to the table a complex set of cultural interests and biases. Hence, CRT seeks to root its theoretical work in the particular and concrete, daily, lived experience of peoples of color.

To make matters even more complex, CRT is self-aware that race is not the only arena of lived experience in which oppression occurs. In the early 1990s Kimberlé Crenshaw introduced the concept of “intersectionality” to describe more complex experiences of oppression.[7] A black female living below the poverty line, for example, lives at the intersection of racism, sexism, and classism. At one level, intersectionality is simply an attempt to accurately describe the threefold confluence of oppression that this particular woman is experiencing. That said, critics of CRT argue that, in CRT circles, intersectionality functions as more than simply a descriptive tool. Instead, critics describe intersectionality as a rhetorical race to the bottom in which the most oppressed person is awarded the most sympathy.

Finally, scholar-activists working within CRT sometimes view themselves as standing within the “radical” tradition of well-known activists like Cesar Chavez, Martin Luther King, Jr., among many others in the abolitionist, Civil Rights, Black and Chicano Power movements.[8] These scholar-activists view themselves as continuous with these figures because of their activist work to transform the relations between race and power. Here they contrast themselves with academics who do not regularly engage in activism. Concrete, praxis-oriented scholar-activism is, for critical race theorists, a matter of course.

Significant departures, however, should be observed. It has already been mentioned that CRT began when scholars concluded that the promises of the Civil Rights Movement would not be realized. In what has become called “Civil Rights 2.0,” it is not uncommon to hear CRT criticisms of Martin Luther King as a leader who was captive to the respect of whites and to the logic of the Constitution which could never deliver on its promises. So, while advocates of CRT may be continuous with these towering historical figures, they are boldly plotting their own ways forward.

Christianity and CRT

There have been a range of Christian responses to CRT. First, the more negative responses tend to dismiss CRT wholesale often because of its philosophical foundations within the Frankfurt school and what has been called “cultural Marxism.”[9] These critics argue that CRT is overwrought in its concerns about systemic oppression and that this all comes from an uncritical acceptance of Marxist theory.[10] Their concerns typically fail (both optically and measurably) to take seriously the lived experiences of people who suffer. Evangelical critics may respond to suffering with acts of charity, but are content to leave the systemic, structural, and reproductive mechanisms of inequality untouched. Their limited and narrowly individualistic conception of sin cannot (or will not) see the ways in which evil embeds itself in networks and institutions of oppression.

Second, while some Christians reject CRT wholesale, others appear to find nothing incommensurate between CRT and their Christian tradition. Many of them will narrate their own life-experiences of racism primarily through the categories of CRT. Biblical and theological categories sometimes appear to be an afterthought. Their intellectual and societal responses to racism appear to largely be directed by the categories and tactics of CRT.

Third, some Christians attempt to forge a moderate path of avoiding either a wholesale rejection or embrace of CRT. Some adopt what I call a “Christ and CRT in paradox” approach. A number of Southern Baptists, for example, are open to listening to some aspects of CRT (because of general revelation, they explain), but ultimately see too much doctrinal incompatibility.[11]

For a variety of reasons, some of which I will discuss below,[12] I find these three responses unsatisfying. In my own theological exploration of race and CRT, I have sought to develop a fourth option. In so doing, I have found unlikely and unexpected resources within the Reformed tradition.

CRT and Reformed Theology in Dialogue

The sovereignty, law, and justice of almighty God flows throughout the world’s complex societal systems and structures.[13] The grace and mercy of Christ impacts the academy, politics, marketplace, and every community and institution within society. The power of the Holy Spirit knows no institutional boundaries or limits. The work of God’s justice is pervasive, cultural, and cosmic in scope. God’s Word and power will not be limited to individual hearts, minds, or souls. All things are being reconciled to God through the cross of Christ and in him all things will be made new.

Early on in my pastoral and theological development I came to the conclusion that the Reformed tradition’s holistic theological vision of justice and culture had something important to offer to contemporary discussions of race that were increasingly structural and systemic. I sensed that Christians wrestling with CRT in both the academy and society could benefit from the resources found within the Reformed tradition.

One particular stream of Reformed theology that shares some fascinating resonances with CRT is that of Neo-Calvinism. This particular stream is extremely critical of western modernity and its oppressive claims of neutrality and universality. In contrast, this stream emphasizes a sensitivity to the perspectival diversity and particularity of different human communities. It resists attempts to assimilate deep difference through societal systems of power (political, cultural, or institutional). Both CRT and Neo-Calvinism argue for the liberation of diverse perspectives from under the oppressive universal claims and systems of western modernity. Abraham Kuyper’s Neo-Calvinist lecture entitled “Uniformity: The Curse of Modern Life” is an excellent case in point.[14]

The remainder of this essay represents a brief attempt to explore what a critical and constructive dialogue between CRT and Reformed theology might look like. The two unlikely conversation partners, as we will soon see, share important resonances that cannot be ignored. In the pages that follow we will also explore how these two traditions would do well to learn from one another.

Mutual Critique of Modern Western Liberalism

The west has placed its faith in the modern liberal tradition and its promise to maximize the freedom of all individuals. According to the modern faith of liberalism, racial justice will be achieved when society fully accepts that ideals and language of liberalism—all men are created equal. If we give liberalism enough time, if we allow it to rule, educate, and pervade our civil discourse, historical progress toward racial justice will be the natural result.[15] This is the modern western faith in liberalism.

CRT is no friend of liberalism. The promises and legislative protections of liberalism can be and have been manipulated to serve the powerful at the expense of the vulnerable. Derrick Bell argues that minorities must reject liberal optimism and assume a racial realism about the ways in which liberalism ignores and even perpetuates racial inequality. Bell asserts “that the whole liberal worldview of private rights and public sovereignty mediated by the rule of law needed to be exploded.” Its worldview “is an attractive mirage that masks the reality of economic and political power.”[16] According to CRT, the forces of racism and liberalism actually combine to twist our institutions, our imaginations, our economies, and our social relations.

Reformed theologians describe the pervasive effects of sin using comprehensive terms that are strikingly similar to CRT. Consider, for example, Abraham Kuyper’s remarks on the connection between sin and systems, evil and social structures. He is speaking here specifically about how human sin took on institutional form in the structures of modern western politics and economics:

In time, both error and sin joined forces to enthrone false principles that violated human nature. Out of these false principles systems were built that varnished over injustice and stamped as normal that which actually stood opposed to the requirements for life… The stronger, almost without exception, have always known how to bend every custom and magisterial ordinance so that the profit is theirs and the loss belongs to the weaker. Men did not literally eat each other like cannibals, but the more powerful exploited the weaker by means of a weapon against which there was no defense.[17]

The Neo-Calvinist doctrine of sin displayed here is profoundly structural and systemic in its scope. Evil is understood, not simply as an individual action or disposition of the heart, but as an institutional and cultural virus that is pervasive. From sin, Kuyper argues, “systems were built that varnished over injustice.” On this point the resonance between Kuyper and Bell is striking. Additionally, on this point, Kuyper appears to be a breath away from structural formulations of evil that can commonly be found in 21st century Black and Latinx liberation theologies.

Mutual Affirmation of Cultural Wealth

Historically speaking, the modern West has looked down on communities of color and the “developing world.” Consciously or unconsciously, it has largely accepted the dogma of Western superiority and, in so doing, it has framed the global other in terms of perceived cultural deficits. So framed, the modern West is always the rescuer, and the global other is always the rescued.

This kind of deficit thinking was challenged by education scholar, Tara Yosso, in 2005.[18] Deficit thinking is a blind spot in scholarship which causes educators to characterize pedagogical work as supplying what students lack. The educational experience of students from communities of color diverges from the presumed norms that inform, for example, educational policy. Yosso’s critical lens is aimed at those norms. She defines community cultural wealth over and against deficit thinking. She describes it as, “an array of knowledge, skills, abilities and contacts possessed and utilized by Communities of Color to survive and resist macro and micro-forms of oppression.”[19] This cultural wealth includes the following: resiliency in aspiration, lingua-cultural skills, the sense of belonging from robust family systems, a sense of history, and ethical formation engaging inequality. Educators, she argues, should recognize these forms of cultural wealth.

Sadly, more often than not, the Western church has not only accepted modern deficit thinking, but it has also actively strengthened it in theology and public life. The history of global missions is marked by a back and forth about deficits and wealth in global cultural contexts.[20] Informed by deficit thinking, Christian giving can frequently be little more than charity. Similarly, Christian action can fail to dismantle the structural machinery that propagates global inequality. Deficit thinking in the church forecloses on the possibility of meaningful cross-cultural dialogue, partnership, and mutual exchange between Christian communities. Always looking to fill the perceived deficits of others, Western and white Christians fail to see their own need for the cultural assets and wealth that communities of color possess. As we will soon see, Reformed Christians are not innocent bystanders here. They have often accepted deficit thinking uncritically and, more than that, have actively perpetuated cultural ideas, doctrines, and political systems that actively harm communities of color.

Deficit thinking is theologically problematic, but it is also biblically puzzling. Scripture repeatedly uses the phrase, “wealth of nations” and other related ideas (Ps. 105:44; Is. 60:11, 61:6, 66:12, 20; Hag. 2:7; Zech. 14:14; Rom. 15:16; Rev. 21:26). The usages refer to material and cultural wealth of distinct cultures and nations beyond Israel. In Scripture, their diverse cultural productions and offerings are made pleasing to God. The Reformed eschatology of Richard Mouw in particular highlights the theological, cultural, and public implications of this biblical truth.[21] If the cultural wealth of Ghana and Guatemala, the Emirates and the Philippines will all be welcomed into the new Jerusalem, how might this challenge the deficit thinking that is so pervasive in white and western Christianity today?

Reformed Theology from the Underside

In this section I want to explore how a conversation with CRT might bear fruit within the Reformed tradition. Yosso has argued that oppressed communities develop a unique moral clarity and insight about the nature of injustice. Survivors of the Holocaust joined the struggle for Civil Rights. Survivors of Japanese interment and Chinese exclusion decried the mistreatment of migrants at the US southern border. Their experiences of oppression and the moral insight it produces is a profound cultural and intellectual asset that leaps off the protest sign and takes up residence in a nation’s memory and imagination. Reformed Christianity needs this.

Allan Boesak is a Reformed theologian and a black South African who was deeply invested in the anti-apartheid movement. Black South Africans like Boesak who struggled during apartheid produced profound works of political, prophetic, and theological clarity. Boesak’s theology and his life demonstrate the power of asset thinking and is—in and of itself—a profound theological asset. Boesak’s life and work is a gift of cultural and theological wealth for the global Reformed community.

Consider the following words from Boesak. He offers a harsh prophetic critique, not simply of apartheid, but of Reformed Christianity’s systemic complicity in its structural evils. Reformed readers could receive these words as a stinging rebuke (as they should) but they should also receive Boesak’s rebuke as a gift of cultural wealth from a brother who possesses moral insight and theological wisdom to offer. Boesak writes,

It is Reformed Christians who have spent years working out the details of apartheid, as a church policy and as a political policy. It is Reformed Christians who have presented this policy to the Afrikaner as the only possible solution, as an expression of the will of God for South Africa, and as being in accord with the gospel and the Reformed Tradition. It is Reformed Christians who have created Afrikaner nationalism, equating the Reformed tradition and Afrikaner ideals with the ideals of the kingdom of God. It is they who have devised the theology of apartheid, deliberately distorting the gospel to suit their racist aspirations. They present this policy as a pseudo-gospel that can be the salvation of all South Africans.[22]

How should Reformed Christians respond to Boesak’s prophetic critique? He prescribes prophetic action. “Reformed Christians are called on not to accept the sinful realities of the world. Rather we are called to challenge, to shape, to subvert, and to humanize history until it conforms to the norm of the kingdom of God.”[23]

Forged in suffering, Boesak’s calls for an active form of fidelity to the Reformed confessions that are practical and public, rather than merely intellectual or personal. What do 16th century Reformed confessions have to do with 21st century racism? Boesak reflects on the first question and answer of the Heidelberg Catechism and applies it directly to the dehumanizing experience of black South Africans. He keys in on the catechism’s insistence that our bodies and souls belong to Jesus Christ alone. Boesak’s writing crescendos as he describes in moving detail the suffering of black bodies and souls under systems of racism and oppression.[24] To assert one’s belonging to Christ is to directly contest and subvert the institutional control and violence of apartheid. Boesak’s method here situates the Reformed confessions within the context of real, lived experiences of racial injustice.

By contrast, during the Civil Rights Era, some white Reformed churches in the American Midwest limited discussions of racism to “a matter of the heart.”[25] Many Reformed Christians continue this line of thinking today. Boesak’s lived struggle on the underside of power produced profound moral and theological insights on the public calling of a Christ-follower amidst systems of racism. The theological wisdom of Boesak’s insights are freely available to the children of white Reformed churches who are looking for resources to navigate contemporary conflicts over race and CRT. The cultural wealth is there, if they will take it.

Conclusion

As I write this chapter, North American Christians are processing and responding to the deaths of three African Americans at the hands of police: Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd. Their deaths have been met with what I consider to be a novel and uncharacteristic outpouring of support by white Christians. The use of #blacklivesmatter is now more fashionable than ever before. As long as the hashtag and the rhetoric of CRT is little more than a sentiment, it will require nothing of the students who use them. Sadly, universities can train students to employ liberative rhetorics without preparing them for the long and hard work for liberation off campus. There is a comfortable safety that can be found in rhetorical wordplay and theoretical abstraction.

Like CRT, Reformed theology can fall prey to the dangers of abstraction, inaction and self-centered comfort that hyper-doctrinarism produces. Students of Reformed theology can easily be tempted to sit back in self-satisfied intellectual analysis of racism and CRT. They can comfortably affirm aspects of CRT by using the theological doctrines of general revelation and common grace. Or they can comfortably dismiss CRT asserting a clean antithesis between the gospel of Jesus and the gospel of Marx.

If Reformed Christians are going to deeply engage racist systems and structures with their minds and their hearts, their ideas and their institutions, they are going to need to go beyond abstract theological or sociological reflection. They are going to need to actively listen to and learn from the embodied struggles of their brothers and sisters on the underside of these systems of power. They must do more than casually read the prophetic witnesses of Boesak and the Belhar and Accra Confessions. They are going to need to actively engage in Reformed action themselves. After all, the best Reformed theology has always been done in the streets be it in Geneva or Cape Town.

Originally published in Reformed Public Theology, ed. Matthew Kaemingk. Published by Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group. Copyright 2021. Used with permission.

Footnotes

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, experience of anti-Asian racism prompted me and a group of Asian American Christian leaders to author a statement against racism and create a collaborative seeking to confront it. See www.asianamericanchristiancollaborative.com. ↑

- Scholars have asked why colleges and universities tout Asian American and Pacific Islander diversity statistics when, for example, their AAPI students experience lack of support and disproportionately negative mental health outcomes while on campus. Julie J. Park and Amy Liu, “Interest Convergence or Divergence?: A Critical Race Analysis of Asian Americans, Meritocracy, and Critical Mass in the Affirmative Action Debate,” Journal of Higher Education 85, no. 1 (January/February, 2014): 36–64, https://juliepark.files.wordpress.com/2009/03/park-liu-aff-action-jhe.pdf. See especially the illustrative discussion of “interest convergence” (a key tenet of CRT) in the article. ↑

- Here are a few examples:

- Duane Terrence Loynes, Sr., “A God Worth Worshipping: Toward a Critical Race Theology” (PhD diss., Marquette University, 2017).

- Nathan Cartagena, “What Christians Get Wrong about Critical Race Theory,” Faithfully Magazine, April 2020, https://faithfullymagazine.com/critical-race-theory-christians/.

- Aida I. Ramos, Gerardo Martí, and Mark T. Mulder, “The Strategic Practice of ‘Fiesta’ in a Latino Protestant Church: Religious Racialization and the Performance of Ethnic Identity,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 59, no. 1 (March 2020): 161–79.

- Brandon Paradise, “How Critical Race Theory Marginalizes the African American Christian Tradition,” Michigan Journal of Race and Law 20, no. 1 (Fall 2014): 117–211

- Robert Chao-Romero, Brown Church: Five Centuries of Latina/o Social Justice, Theology, and Identity (Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2020).

- As an example, CRT is applied in educational studies. Malcolm Knowles proposed traits of an “adult learner.” According to Knowles, adult learners need to know why they are learning something, want to learn through experiences, learn by solving problems, and need to feel the relevance of what they are learning. See Malcolm S. Knowles, Elwood F. Holton, and Richard A. Swanson, The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development, 7th ed. (New York: Routledge, 2012). His description of an adult learner has been judged by Critical Race Theorists (who refer to themselves as “crits”) to have overlooked learning dynamics related to race and ethnicity. Knowles evinces cultural blindness to norms, customs, values, and ways of being in learners of color. His resulting theory of adult learning (androgogy) would then be insufficient in educating for diversity. See, Stephen D. Brookfield et al., Teaching Race: How to Help Students Unmask and Challenge Racism (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2019). ↑

- “Whiteness” is here used in the sense that Willie Jennings has offered. He writes, “No one is born white. There is no white biology, but whiteness is real. Whiteness is a working, a forming toward a maturity that destroys. Whiteness is an invitation to a form of agency and a subjectivity that imagines life progressing toward what is in fact a diseased understanding of maturity, a maturity that invites us to evaluate the entire world by how far along it is toward this goal.” Willie James Jennings, “Can White People Be Saved? Reflections on the Relationship of Missions and Whiteness,” in Can “White” People Be Saved? Triangulating Race, Theology, and Mission, ed. Love L. Sechrest, Johnny Ramírez-Johnson, and Amos Yong (Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2018), 34. The editors of the volume in which this essay is found helpfully add that whiteness is “an idolatrous way of being in the world at its core and thus activating a question that any reader needs to confront about the degree to which one’s own praxis and worldview yearns for or participates in whiteness.” Johnny Ramírez-Johnson and Love L. Sechrest, “Introduction: Race and Missiology in Glocal Perspective,” in Can “White” People Be Saved?: Triangulating Race, Theology, and Mission, ed. Love L. Sechrest, Johnny Ramírez-Johnson, and Amos Yong (Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2018), 13. ↑

- Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic, Critical Race Theory: An Introduction, 2nd ed. (New York: New York University Press, 2012), 22. ↑

- Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color,” Stanford Law Review 43, no. 6 (July 1991): 1241–99. It is important to note that when Crenshaw articulated the concept of intersectionality it was those she referred to as “liberals” who sought to empty discourse of racial, gender, and other identitarian distinctives. ↑

- Delgado and Stefancic, Critical Race Theory, 5. Chavez and King were selected for mention from among the list of radical activists, for the most part, because of their explicitly Christian confession and spirituality. ↑

- See, for example, Neil Shenvi, “The Incompatibility of Critical Theory and Christianity,” The Gospel Coalition, May 15, 2019, https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/incompatibility-critical-theory-christianity/. See also its origins in William Lind, “The Roots of Political Correctness,” The American Conservative, November 19, 2009, https://www.theamericanconservative.com/the-roots-of-political-correctness/. ↑

- Whether such skeptics are right to be concerned falls outside the scope of this chapter. It seems important, nevertheless, to name this dynamic. ↑

- Southern Baptist Convention, “On Critical Race Theory and Intersectionality,” SBC 2019 Annual Meeting Resolution 9, June 12, 2019, Their “categories identified as sinful in Scripture” is cryptic. Some consider the very idea of race to be a sinful category. ↑

- For a more in-depth theological reflection on these options see Jeff Liou, “Much in Every Way: Employing the Concept of Race in Theological Anthropology and Christian Practice” (PhD diss., Fuller Theological Seminary, 2017). ↑

- Of course, none of these Reformed affirmations overlook the reality of sin and brokenness which also flow throughout the world’s systems and structures. ↑

- Abraham Kuyper, “Uniformity: The Curse of Uniformity” Kuyper Centennial Reader ↑

- Anecdotally, the number of times “progress” in race relations was mentioned in my seminary course on Martin Luther King from 2016 to 2020 has dropped to zero. This, however, is not to neglect the important economic analyses that focus on the correlations between neoliberal economics and the alleviation of global poverty. The paragraph for this footnote focuses instead on constitutionalism more generally. ↑

- Derrick Bell, “Racial Realism,” Connecticut Law Review 24, no. 2 (Winter 1992): 363–80. ↑

- Abraham Kuyper, The Problem of Poverty, trans. James Skillen (Sioux Center, IA: Dordt College Press, 2011), 31–32. ↑

- Tara J. Yosso, “Whose Culture Has Capital? A Critical Race Theory Discussion of Community Cultural Wealth,” Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Education 8, no. 1 (August 2006): 69–91. ↑

- Ibid., 69. ↑

- See, for example, Henry Morton Stanley, In Darkest Africa: or the Quest, Rescue, and Retreat of Emin, Governor of Equatoria, 2 vols. (London: S. Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington, 1890). See also, William Booth’s rebuttal in the same year, William Booth, In Darkest England: and the Way Out (New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1890). ↑

- See Richard J. Mouw, When the Kings Come Marching In: Isaiah and the New Jerusalem (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002). ↑

- Allan Boesak, Black and Reformed: Apartheid, Liberation and the Calvinist Tradition (New York: Orbis, 1984), 88. Do not think that the World Alliance of Reformed Churches’ official anti-Apartheid declaration settled the matter in 1982. Its North American rebranding in the form of “Kinism” was declared a heresy by the Christian Reformed Church of North America in 2019. Kinism attributes its segregationist theology to Calvin, Kuyper, and Berkhof. Students of these Reformed figures should be prepared to produce a roadmap that actively leads away from, not towards, racial injustice. Without such preparedness, what guarantee can there be that the vulnerabilities will not be exploited again? ↑

- Ibid., 90 ↑

- Ibid., 97. ↑

- Eugene P. Heideman, The Practice of Piety: The Theology of the Midwestern Reformed Church in America, 1866-1966, The Historical Series of the Reformed Church in America (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009), 251. ↑