Did Jesus legitimize the concept of a secular state? Many people, including well-intentioned Christians in today’s polite society, seem to think so. The “proof-text” they point to is Christ’s famous retort in St. Matthew’s Gospel, “render unto to Caesar that which is Caesar’s, but render unto God that which is God’s.” Yet a closer examination, especially of the Old Testament context and current which would have informed Christ’s own view, suggests otherwise.

Various commentators and ideologues, seeking to find scriptural warrant for the religiously neutral or secular state, will immediately gravitate to this passage as if it is set in stone. It has become increasingly popular in secular writings to argue that the origins of secularism go back to Christ and Christianity. Of course, the purpose for this deceitful claim should be self-apparent.

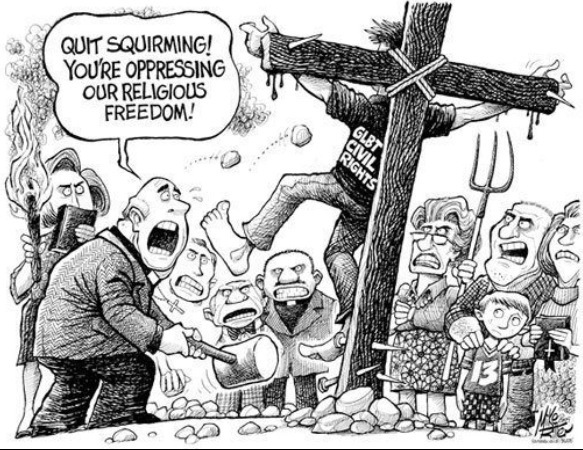

The standard secularist interpretation is premised on the modern presupposition of the privatization of religion. But religion is never a private affair. Moreover, Christianity, by its very commissioning by Christ, can never be a private religion. Throughout all human history religion has been a deeply public affair. There was never a society, until recently, that conjured up the private-public dichotomy which weaponizes Holy Writ to back it up. The intention is clear: Secularists cite Scripture when it suits them to box out Christians from the public sphere and seize control of the public vision for society. When there are no Christians left, they will not cite Matthew’s Gospel or Christ’s words for anything to legitimize their anti-God and anti-Christian agenda.

Another reading of Christ’s witty remark to the Jewish leaders of His day was that He stumped them and prevented them having Him fall into the trap they had attempted to set. Christ’s statement, thus, is not revolutionary or setting a new mantle for us but deeply tied to the Old Testament reality which Christ had come to fulfill.

When Lot and his family fled Sodom to safety, Lot’s wife looked back and was turned to salt. The Church Fathers interpreted this to be a judgement against the heart’s perverse desires to remain in such an ungodly place. Lot’s wife, according to Augustine, sighed in agony in looking back at Sodom—upset at what she was leaving though God had a greater place to bring them. She died because of her yearning to be under the yoke of sin and the false pleasures offered by the City of Man.

When God instructed Moses and the Israelites to leave Egypt, they were instructed not to look back and yearn for Pharaoh’s rule. Indeed, the grumbling of the Israelites in the desert—which contested, not Moses’s leadership, but God’s—was because they would rather have died slaves in Egypt than struggle to walk with God as Abraham did. God plucked Israel out of slavery in Egypt so that they could be totally devoted to Him. They were to have no allegiance to Pharaoh, just as Lot and his family were to have no allegiance to Sodom.

God repeatedly warns the Israelites not to become like the other nations, and yet that is what they do. And when the Israelites elect their king in place of God, God tells the prophet Nathan that “they have not rejected thee, but they have rejected me, that I should not reign over them.” This is the ultimate want of the secularists, to strip down God and utterly reject Him and replace Him with their own conception of the divine on earth. Secularists seek a return to Sodom or Egypt, and they have the audacity—with all the credibility of their doctorates and well-praised books—to claim that the return to slavery is entailed by Scripture itself.

When God is not in the hearts of the Israelites they are reduced to nothingness. They suffer famine and pillage. They suffer civil war and dispossession. And they suffer under the yoke of tyranny, especially the tyranny of the many “caesars” in Old Testament history, from Pharaoh to Eglon to Antiochus. Even Herod was nothing more than a tyrant puppet installed by the Romans to administer the province on behalf of the ever-expanding Roman imperial system.

If the state is not also subordinated to the law and will of God, the nation will suffer judgement. This is what Christ, through David, teaches in the Psalms. Those nations who are filled with wicked and perverse men who forget God and indulge in their own lusts and fantasies will be hewn down and cast into hell. Nations are blessed when God is at their center. Nations are consumed and cast away when they reject God and make themselves the deities to be worshiped.

The Old Testament is clearly against submission to earthly authority when that earthly ruler (or state itself) becomes one’s god and boxes God out of public life. State worship and kingship is considered a form of idolatry, from which God needed to constantly liberate the Israelites so that He could redirect their hearts and labor to the true Well of Life. The same is as true today as it was back then. The secularist disposition is to carve out that idolatry and, through a deceitful use of Christian Scripture and tradition, shackle Christians to partake in this idolatry in the form of submission to the new Caesar.

Christ often spoke and taught in parables and witticisms. The parables were often a stumbling block to the unfaithful. They remain a stumbling block to the unfaithful today who manage to think that they legitimize their sinful and blasphemous desires. The tradition that Christ spoke of to the Israelites through the Prophets, David, and Asaph, and that was recorded by Moses and the other Old Testament writers, is that the state is owed nothing. God is owed everything. The state, insofar that it has any legitimacy—all of which comes from God—also owes God everything.

Within the context and tradition of the Old Testament, Christ’s remark, “Render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s, but render unto God that which is God’s,” does not necessarily legitimize Caesar at all. Instead, it can be understood as a witticism that shows total devotion to God, because everything is owed to God as the Old Testament history reveals. The faithful would have immediately understood that. What is owed to Caesar? Christ doesn’t actually say.

We cannot have a common good without the recognition of to whom the common good is directed in worship and faithfulness—namely, God. If this is a bridge too far for Christians today, then how can we call ourselves His disciples?