Under the umbrella of pragmatism, Owen spoke about using “Islamic style,” but as this study demonstrates, it actually morphed into Islamic thought forms and into a promotion of an Islamic worldview. It appears that he has served the Islamic agenda more than a Christian one…. The case study calls for a higher level of accountability of translators, translation agencies, mission agencies and their staff.

Summary

This case study surveys what influenced the development of a Muslim-friendly Arabic rendition of ‘The Life of the Messiah,’ as well as how it has influenced other translations of the Bible. The study uses David Owen’s Sirat al-Masih to demonstrate that ‘ideas have consequences.’ It observes that under the umbrella of pragmatism, Owen spoke about using “Islamic style,” but actually it morphed into Islamic thought forms and into a promotion of an Islamic worldview. It appears that he has served the Islamic agenda more than a Christian one.

1. Introduction

…and behold, a voice out of the heavens said, “This is My beloved Son, in whom I am well-pleased.” (Matt 3:17 NASB)

A voice came from heaven saying, This is The Beloved and We are very pleased with him! (Dove 26:20)[1]

In 1987, David Owen working under his independent mission, “Project Sunrise,” introduced his new ‘Muslim-friendly’ Arabic “Sirat al-Masih” (Sirat) that is “The Life of the Messiah,” with these words:

One of our hopes is that Project Sunrise will stimulate a new movement of Bible translation making use of Islamic-styled Arabic of literary quality in which each piece of work will build on the efforts of the previous one.[2]

In this case-study we will examine the history of the development of David Owen’s groundbreaking ‘The Life of the Messiah,’ how it influenced select translations of the Bible, and how they were used to promote the Insider Movement, whose advocates claim that Muslims who convert to Christianity should remain Muslims in practice. We will note the factors that permitted this ‘translation’ also permitted it to flourish both then and now, and the lessons that the global Church can learn from it. The ideas that influenced David Owen’s production of his Islamized ‘The Life of the Messiah’ continue to have effects today, especially in the production of Muslim Idiom Translations (MIT) of the Bible. For all of their supposed benefits, they have actually served to undermine both the honor due to the Triune God and the global Church in its evangelism and discipleship efforts.

2. ‘The Mother of the Books’ Defined

In Islam, the term umm al-kitÄb (mother of the book) refers to the tablet in heaven from which all revelations have their source. This thinking is derived from a number of suras which refer to a preserved tablet.[3] For example: Allah doth blot out or confirm what he pleaseth: With him is the mother of the book (umm al-kitÄb) (Q. 13:39; also, 43:3-4; 56:77-80; 85:21-22).

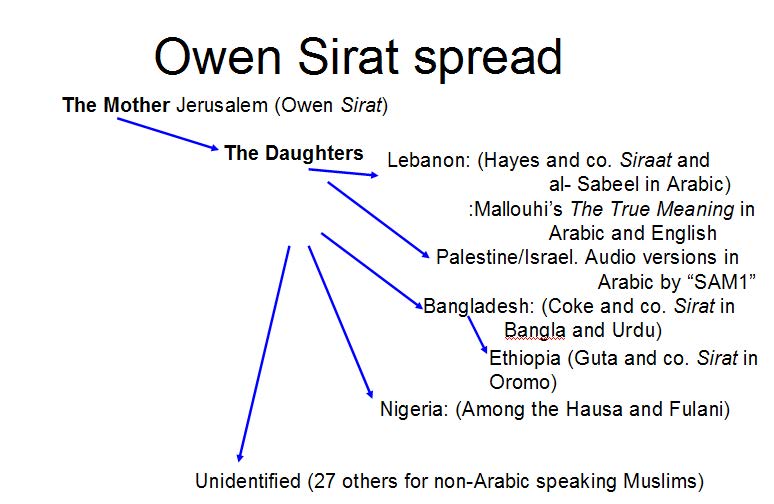

Thus, we attribute an Islamic term to an Islamized rendition of the Gospels, and, with tongue in cheek, call it The Mother of the Books. The following figure illustrates some of the ‘offspring’ of the Sirat which include ‘idiomatic translations’ for Muslim audiences, or Muslim Idiom Translations (MITs), as well as “highly-creative scripture-use products” that his seminal work has yielded.[4]

3. The History of “Project Sunrise”

In September 1987, David Owen sketched out his biography which includes studies at a “California seminary” (1973-1976) during what he called his ‘formative phase.’[5] During this time at Fuller Seminary, Charles Kraft was teaching and publishing his materials on receptor-focused communications and dynamic-equivalent churches.[6] Kraft’s and others’ teachings opened the Pandora’s Box for avant garde missiologists who considered that mosques and churches could be said to be dynamically equivalent. A correspondent writing about this era at Fuller, noted, “Arabic Sira is, and was, a faithful example of the ‘contextualization’ taught by Fuller Seminary in the 1970s.”[7]

One of his fellow students, who would later defend the usefulness of his Sirat, would go on to work among the Hausa in Nigeria.[8] At the same time Owen began to attend mosque activities in Los Angeles.

Through his ‘formative phase’ Owen became convinced of the need for ‘a willingness to travel new paths in mission.’[9] This was also the idea of a book written by another Fuller student about this time, Phil Parshall. Parshall’s 1980 DMiss thesis was published as New Paths in Muslim Evangelism.[10] In this book, Parshall expressed the idea “the closer we can relate to Muslim forms, the more positive will be the response to our message, particularly in initial instances of evangelistic effort….”[11] As we will see, Owen defended the same idea in his Sirat.

During this phase and subsequent exposure in the Arabic world, Owen set out to “pinpoint the problem of the failure of the Church in fulfilling the Great Commission in the Islamic world” and in his words, “something has gone drastically wrong.”[12] Owen was not the first to examine missionary results among Muslims, as already in 1926, Walter Fairman, writing in the Moslem World, remarked,

There are no Moslem lands today where something is not being attempted to win Moslems to Christ. Yet relatively, and actually, very little has been accomplished…. The failure is on our part and the secret must lie in the method we have hitherto adopted…[13]

Whereas Fairman concluded that the controversial or polemical approach of tearing down tear down Islam was at fault, Owen concluded that “the root of the problem lay in a weak tradition of Arabic Bible translation,” and that with respect to translation, the church “was never on the track in the first place.”[14] He found further support in a pre-1948 document, that advocated the production of a Muslim-friendly ‘targum’ that could be used alongside of existing translations, and he reproduced the text of that document in the “Publication Report.”[15]

Owen found financial support from Blackstone Presbyterian Church in Durham, North Carolina, and established himself in the Middle East with the solid conviction that he would be instrumental in creating “a movement for Jesus inside Islam – a ‘haraka Isawiyya.’”[16] With even more boldness he likely included himself when he stated, “the framework for such a movement has been sovereignly set and is only waiting for creative, Spirit-lead harvesters to fill it out.”[17]

From 1982-1987 Owen received a work permit in Jerusalem through the local Bible Society as a ‘Researcher for Muslim Audiences.’[18]Around this time he also received financial help from an Assembly of God missionary based in Jerusalem, and endorsements of his ideas by another denominational American missionary based in the area as well.[19] Thus with the theological ideas from Fuller Seminary, finances from a USA-based local church and a Jerusalem-based missionary, endorsement from another missionary, freedom to act in his own independent mission, backing from the Bible Society, the historical precedent of the need for a targum, and a conviction of divine approval, Owen set out to produce his ‘The Life of the Messiah.’

3.1 The Content of Project Sunrise

Following Tatian’s Diatessaron, or Harmony of the Four Gospels, Owen worked with a former-Muslim Palestinian poet named Adnan Baidun [alt. Baydoon] to “prepare a ‘Gospel’ for the Muslim reader.”[20] The 1987 Arabic version can be found on-line, here,[21] and the English text of the thirty-chapter work can be found here.[22] In a nutshell Owen suggested that a “contextualised Bible translation for the Muslim Arab world primarily calls for the use of Islamic theological terminology coupled with a high level of literary Arabic. The goal is a dynamically equivalent presentation of Scripture for the Muslim Arab readers of today.”[23] The work followed a rhymed prose or saja’ [alt. sajÊ¿] style and assonance of the Qur’an.

By 1987 the fifth rendition had been produced and the “Publication Report” set out to defend the word choices and the theological underpinning for the work. In a few words, this and other “Special Bible translation projects” would be “the foundation for a messianic movement in Islam.”[24] Owen used the genre of biography, not unlike the Life of Muhammad [Ar. SÄ«rat rasÅ«l Allah] from Ibn HishÄm/ IsḥÄq or other lives of the prophets along with Islamic conventions like introducing each chapter with the basmala (in the name of Allah) along with places where they were revealed. By doing so he envisioned that these would greatly aid the acceptability of Christian literature in the Muslim world and serve to remove stumbling blocks to acceptance of the Gospel.[25]

Furthermore Owen used the platform of the journal of Arab World Ministries (AWM), Seedbed, to advance his agenda, in articles that appeared in 1986, 1987 and 1988.[26] His 1991 article, under the initials ‘D.O.,’ “A Jesus Movement Within Islam” was featured in Interconnect, a journal for missions to Muslims, based in Phoenix, Arizona.[27]

By invoking historical precedent, supposedly massive failures of the church, and divine warrant, while using the resources of Seedbed and Interconnect magazines along with those of his supporting church and local missionaries, Owen launched his project.

3.2 Project Sunrise Gets Debated

In 1988 the Seedbed editor Samuel Schlorff coordinated a number of responses to Owen under the title of “Feedback on Project Sunrise (Sira): A Look at ‘Dynamic Equivalence’ in an Islamic Context.” Schlorff collated material from some eighteen respondents and the input was widely varied, ranging from ‘easily readable’ to this is an “expurgated version [which] distorts the perspective of Biblical revelation” and this same Christian respondent of Muslim background asserted, “Muslims are not fools.”

In 1989 and 1990 someone using the initials MB — [now known as Dr. Mark Beaumont presently of the London School of Theology]—conducted some careful scrutiny under the titles of “Jesus in ‘Sirat ul-Masih’” (sic) and “Qur’anic Style in Sirat ul-Masih.” (sic) Beaumont examined the Arabic text of the Sirat’s Lord’s Prayer and at one point stated, “what Jesus intended to teach is distorted and lost.”[28] Although Owen had affirmed in 1987 that the project would exhibit “Commitment to the Great Commission” and “The Guidance of the Holy Spirit” Beaumont’s words would suggest that the Sirat fell short of those goals.[29]

Beaumont further examined the Sirat in his doctoral thesis and challenged Owen’s assertion, which has been repeated almost verbatim by Rick Brown of Wycliffe/SIL, namely that it is better not to use Father in the Sirat because in order “to avoid crude, anthropomorphic misinterpretations by Muslim readers, the Father-Son metaphor is retained only where the context itself explains its significance.”[30]

Beaumont and the respondents in Schlorff’s Seedbed article examined the statement by Owen, “Jesus was a Semite, and the original language of Jesus’ teachings was a combination of Aramaic and Hebrew. To communicate to other Semitic peoples we may at times have to go behind the language of the Greek New Testament to its Aramaic-Hebrew origins in exegeting certain passages for our readers.”[31] They observed that the idea of going “behind the language” could open up all kinds of subjective and creative translation choices.

Owen affirmed, “we also feel an absolute commitment to include believers in Christ from a Muslim background in the translation process.”[32] To what extent he did this, outside of using the services of Adnan Baidun is not known, but what is known is that other Christians of a Muslim background have identified the following worrisome, qur’anic and Islamic influences on the Sirat.

(1) From his ‘sura’ called ‘The Word’

-

- v. 5—“But those who believed are the companions of Allah and they are the ones who are saved.” Normally the ‘companions of Allah’ (Ar. á¹£aḥÄba) are the few faithful Muslims who stayed with Muhammad through thick and thin. Now this term is applied to Christians.

(2) From ‘The Family of Dawud’ [Compare this to qur’anic suras which are named “The family of… Ê¿ImrÄn” etc.]

-

- v.8—John the Baptist will lead the people back to “those who have been guided.” A term to describe Muslims, who self-identify as the ‘guided ones’ (Ar. al-muhtadÅ«na) who walk in the ‘correct path’ (Q. 2:157) is applied to the children of Israel who will repent.

- v. 16—a phrase quoted verbatim from Q. 3:45 is applied to Jesus. “He will be eminent (Ar. wajÄ«hÄn) in both this world and in the next.” This obscures the Islamic macro-context of Sura 3, asserting the oneness of Allah, and effaces the fact that Muḥammad always eclipses the honor of Jesus in Islamic theology.

- v. 40—John the Baptist was said to have brought the people “a clear message.” In Islamic thinking those with the ‘clear’ Qur’an have ‘clear thinking’ and those outside of Islam are in the darkness and obscurity of unbelief (Ar. jÄhiliyya).[33]

3.3 The Sunset of Project Sunrise

In 1992 Global Publications printed the work under the title Sirat al-Masih: The Life of the Messiah in Classical Arabic with English Translation.[34] An eyewitness who lived in the region wrote that around 1993 he and other missionaries such as Jeff Hayes and Larry Ciccarelli [see below] who were living in Syria at the time were “inventing” their new approach—that is to say, one of radical contextualization—and that “David Owen was a legendary figure.”[35] When detractors like Mark Beaumont came along, however, the project appeared to run out of steam. In the early 1990s, Beaumont could contact neither Owen nor the Palestinian poet for input. By 2001, Owen had withdrawn the copyright for the work and it would have seemed to wither on the vine. At this time, the South African Islamic polemicist, Ahmad Deedat warned Arabs against Owen’s work as he suggested that it was “packaged ‘Islamically’ to deceive Muslims.”[36] The Muslim World League, as noted by Schlorff, issued a warning against the Sirat because it had tried to imitate the so-called ‘inimitable’ Qur’an in style, vocabulary and rhyming. He also reported that the Islamic Research Academy in Egypt asked for a legal ruling from the Sheikh of the main Sunni Muslim University, al-Azhar, to have it outlawed.[37] The project would appear to be finished.

3.4 Worrisome Thoughts From David Owen

Phil Parshall who, in 1989 had enthused over the Sirat with the words “an outstanding example of linguistic and stylistic adaptation to Muslim thought,” became concerned that Owen himself was being Islamized.[38] Parshall reports that Owen said:

I believe that a Muslim-follower of Jesus can repeat [the shahada] with conviction…In a Jesus movement in Islam, Muhammad [would be seen as an OT prophet]. [There are] [r]eferences to violence and polygamy within the OT…. Maybe such a heresy could become a stepping-stone….We cannot be heresy hunters. [39]

Owen’s justification of using ‘heresy’ to advance his strategy is highly problematic. It appears that this posture affected his own spiritual life, with an eyewitness reporting a number of liaisons and ultimately a departure from the Christian faith. [40]

3.4.1 Owen’s Un-hallowed Lord’s Prayer

There is a Latin phrase which says, ‘lex orandi, lex credendi’ (or literally, the law of praying [is] the law of believing). That is to say, the way one prays, is indicative of what one believes, or forms what one believes. This same adage would hold true for those using the Lord’s Prayer of the Sirat.[41] Consistent with Islamic thinking, the ‘Our Father’ is conspicuously missing. Owen’s version of the Lord’s Prayer is also consistent with his assertion that “the culturally-bound confessions of Nicea and Chalcedon will not prove to be an adequate theological support for the Body of Christ in a Muslim context.”[42]

When you do salat,[43] call upon your Lord humbly. AllÄhumma,[44] Lord of all the world, let your great remembrance[45] be lifted up, may your wise command be executed, may your true Din[46] be victorious, in both the invisible and the visible worlds.

Oh Lord, provide for us from your good things according to the need of each day. Oh Lord, forgive us our sins as we forgive those who sin against us. Oh Lord, strengthen us when you test our faith. Oh Lord, deliver us from Shaytan the accursed.

Oh Possessor of authority, oh one full of glory and honor, in all the world you alone are the most strong and firm.

Forgive other people their sins and Allah will forgive yours. For if you forgive the sins of others, surely Allah is the Forgiving and the Merciful.[47]

Whereas it might be thought that Owen was being innovative here, in fact he is standing squarely on the shoulders of Abu Muhammad al-Qasim (d. ca. 860) who also made a translation of the Lord’s Prayer.[48] A Muslim made this translation to win Christians over to Islam.

Our Lord, who is in heaven, may your name and your wisdom be holy; may your rule and your might be great; may your dominion appear in your earth as it appears in your heaven; feed us with bread in our daily need; forgive us our past sins as we forgive those who have wronged us; forgive us in your mercy even though we have sinned; do not, our Lord, inflict on us tribulation, and free us from foul calamities; for yours are the rule and the power, and from you are the dominion and the forgiveness, for ever and ever, world without end.

3.5 Rising From the Ashes, in Another Form and in Other Places

In a circular letter to his friends in 2001, a well-respected missiologist cited a note he had received concerning the Sirat:

My own view is that Sira is one important step along the way toward providing the whole Kitab [Arabic word for book which can mean the Bible] in appropriate style and language. Sira helps clarify the vocabulary and establish the word lists of key terms. Sira can be disassembled and reconstructed into four separate Gospels. We will continue to promote Sira translations.[49]

Personal correspondence with Mark Beaumont, suggests that this ‘translation’ “bears a resemblance” to “the movement spearheaded by Mazhar Mallouhi.”[50] Included in this movement is the 2008 Muslim Idiom work, The True Meaning of the Gospel of Christ.[51] The mission organization, Frontiers, almost completely funded this work. The fundraiser at the time stated the following:

I am aware of no other funding from any other source. Certainly member support for Larry Chicarelli [Ciccarelli] through WBT funded his work on the project, but I believe all direct costs were funded by Frontiers — and likely Larry’s travel and housing costs for project meetings were reimbursed by Mallouhi (through the Al Kalima UK entity). My recollection is that support received by Frontiers was channelled to the UK Al Kalima entity, led by Ed Greening, which paid invoices from the printer and probably all other bills.[52]

Consultation for this project was given by Rick Brown and Larry Ciccarelli of Wycliffe/SIL.[53] Elsewhere Rick Brown has defended his choices for removing Father and Son from translations which have echoes of Owen’s own ideas. This translation by Mazhar Mallouhi is available today at the al-Kalima website.[54] Ekram Lamie Hennawie, past president of the Evangelical Theological Seminary of Cairo, who served on the committee that “oversaw the creation of the True Meaning translation,” also defended this translation.[55]

There is an ironic twist to the story of the Sirat being influential in the background of Mallouhi’s True Meaning. Paul Gordon Chandler reported that Mallouhi found the Sirat to act “dishonestly to the Muslim reader” and it can be seen by them as “an attempt to mislead or deceive.”[56]

In 2008, a Common Ground Consultation was held in Arizona. It strongly advocated the same ‘staying inside of one’s religion’ that Owen had advocated. There, Jeff Hayes, a certified Arabic translator who used to work for—and may still be connected with—the Navigators, distributed a CD containing documents which showed further influence of Owen on Hayes and vice-versa.[57] Hayes produced a list of Muslim Idiom translations and ranked them both by the amount of input that he had had, as well as their usefulness for “starting an insider movement.” He entitled his document “Current Status of Arabic Scriptures with special emphasis on applicability to Insider Movements of Muslims.” This is what he reported about the Sirat:

**Sirat Almaseeh (The life of the Messiah) translated by David Owen (American) and Adnan Baidun (Palestinian), 1987. Chronological harmony of the Gospels. Very Muslim. Language is beautiful, but is less so in the last half (Adnan was not as closely involved). Has missing verses, mistakes, and some added Koranic phrases. Style is rhymed prose suitable for chanting (like Koran…. adapted to insider theological thinking patterns. Has been used in several insider movements around the world in the form of a diglot (local language + Arabic) by Milton Coke (driving force behind the largest Muslim insider movement in the world)…. Appropriate as a starting point for an insider movement. [The two ** convention by Hayes suggests that he has had ‘significant input’][58]

In 2011, SIL produced an internal document entitled “A Typology of Bible Translations for Muslim Audiences.”[59] It compared and contrasted various translation philosophies and then went on to mention Sirat. The brief notes make no critique of the content or the Islamizing of Sirat and its highly problematic rendition of ‘Son of God’ as ‘Beloved,’ but instead, focus on the fact that it lacked SIL consultants. The report reads:

An out-of-print example of a transformational translation is a harmony of the Gospels, Sirat al-Maseeh (“Biography of Christ”), published in 1986. It was a pioneering attempt to use features from the Qur’an, such as rhymed prose and verse numbers formatted as they are in the Qur’an. The key term Son of God is translated as “The Beloved,” and Messiah is rendered as “al-Mahdi” (the rightly guided one, a title for an end-time savior who in some traditions is associated with or identical to Jesus). . . . This translation was creative in addressing worldview issues and key terms, but could have benefitted from exegetical input from a trained consultant because the choices did not always convey the correct meaning. Translations of this Arabic harmony of the Gospels into other languages have been popular, and it seems that in most cases the exegetical problems were corrected in these other language translations.

Whether “exegetical problems” were in fact remedied by other language translations will become more apparent as we observe them below.

3.5.1 And Moves to Bangladesh

The Isa-e-Jamaat group of Bangladesh likely produced the 1999 Arabic/Bengali version.[60] Personal correspondence with an eyewitness, however, suggests that production of the Sirat in Bangla occurred as early as 1988.[61]

What the casual viewer might miss in reviewing Hayes’ documented influence of the Sirat is the fact that he himself suggests that Owen’s Sirat was influential in the formation of Muslim Idiom Translations in Bangladesh. His words as above were as such:

Has been used in several insider movements around the world in the form of a diglot (local language + Arabic) by Milton Coke (driving force behind the largest Muslim insider movement in the world).

WORLD Magazine reported that Milton Coke’s organization, Global Partners for Development, distributed 10,000 copies of the Gospel of Mark against the wishes of the larger Bangladeshi Christian community in 2005.[62] In an article co-authored with Tom McCormick, George King in “Muslim Idiom Translations in Bangladesh” sorts out multiple Bangla versions called Injil Sharif, and defends the use of this Global Partners’ 2005 translation.[63]

To add credence to the Sirat, the former Fuller professor of Islamics, J. Dudley Woodberry in his article “A Global Perspective on Muslims coming to Christ” cites its effectiveness in ‘what God is using in some large movements.’ He mentions a particular one in ‘South Asia’—i.e. Bangladesh—where people “used the Sirat al-Masih (the Life of Christ) with Muslim-friendly terms in a qur’anic style” in outreach to Muslims. [64]

When Darrell Whiteman of the American Bible Society went to Bangladesh in October 2007, he reported—in his words: a ‘Jesus Movement within Islam’ [used four times in the report]—and he defended the Gospel of Mark rendition mentioned above in his report. Could Owen, who also spoke of ‘Jesus Movements within Islam,’ have influenced Whiteman? [65]

The verbal testimony of a Bangladeshi former adherent of the insider movement however, shines light on the intentions of the American Bible Society. Anwar Hossein, who left the insider movement and became the president of the Bangladeshi Bible Society, stated the following on October 4, 2010.

…The IM [Insider Movement] went to the American Bible Society to push the Bangla Bible Society because they know the Bangla Bible Society is getting money from the American Bible Society. They [i.e. Insider Movement proponents] pushed the American Bible Society to tell them [i.e. the Bangla Bible Society] to accept their IM translation.[66]

3.5.2 And to the Urdu-Speaking World

According to ‘SAM2’ the Sirat was translated into Urdu, which is spoken and read in Pakistan, Afghanistan and India.[67]

3.5.3 And Then to Ethiopia

Owen hoped that “each piece of work will build on the efforts of the previous one.” That is, he hoped that one translation as he called them, would build on the next. Likely he did not foresee that his work would extend to Ethiopia, via Bangladesh. An Ethiopian, Olam Belay Guta, wrote his 2003 Fuller dissertation, “Contextualizing the Gospel among the Muslim Oromo.” He recounts his personal experiences in Bangladesh—‘Islampur’—and his interactions with the leaders of the insider movement there, who also travelled to Ethiopia. He notes, “Later on he supported me on the translation of Sirat Al Messiah into the Oromo dialect.” [68] The ‘he’ who is referred to is unknown, but certainly, it would be someone who advocated the usefulness of the Sirat and desired to see it disseminated widely.[69]

3.5.4 And to Lebanon

Jeff Hayes suggests that he had “majority input” in the production of both “The Path” and “The Way,” publications which were revisions of Owen’s Sirat. He describes them as,

***Al-Sabeel (The Path) revision of above [that is to say of Owen’s work] based on suggestions by Lebanon group, 2004. Vocabulary altered to be more insider. Changes solve copyright problems. Digital. To be used in diglots in insider movements who have already started translation. Appropriate as a starting point for an insider movement.

***Al-Siraat (the Way) major revision of Sirat [i.e. Owen’s work] to reflect insider movement terminology in insider movement in Southern Lebanon (expected 2004) – will include Acts 1-2 and be more faithful to content of the gospels. Being done digitally by Lebanese MB; needs grammatical and stylistic revision (to be done). Appropriate as a starting point for an insider movement.

3.5.5 And to Israel/Palestine

According to an eyewitness, the Sirat was done in “Quranic Arabic and meter, and poetry” and was recorded in an Islamic chanting style.[70] It is presently available on-line and the text with a 1987 copyright is available as a PDF in Arabic for download.[71] One of the comments left on the website where the Sirat is available is noteworthy. An Arabic-speaking Muslim writes, “Fear God, this book aims to [aid the] missionary invasion of Islam.”[72] Similar to the Muslim World League’s perspective, this person saw the work as being a tool to invade Islam.

3.5.6 And to Nigeria

‘SAM3’ used this work in Nigeria and relates that it is available in a Christian bookshop in Kano, but is unaware of how it first got there.[73] To the best of ‘SAM3s’ awareness the Sirat has not been used as the basis for any other translation in Nigeria. Comments regarding its use were:

We have found that many staunch Muslims in Africa who read in Arabic take interest in the true Jesus through reading the Sirat and then go on to learn more about Jesus in the Bible, either in Arabic or in another more local language, such as Hausa. Many of them have become sincere and courageous followers of Jesus, willing to suffer persecution for his name and to risk their lives for the spread of the Gospel.

The fuller justification for the use of the Sirat by this correspondent is that its genre of biography serves as a bridge from the “Qur’an into the full Bible.” Whether a work can be justified simply based on its genre is an open question. The “New World Translation” of the Watchtower Society (also known as Jehovah’s Witnesses) might be considered to be in the genre of Bible translations. However, it would be imprudent to suggest that this version with mis-translated passages that exhibit an Arian Christology could be used as a ‘bridge’ to a Bible with a Chalcedonian or orthodox Christology.

3.5.7 And to the Ends of the Earth

A Syrian ‘E.E’ who has worked for a number of international organizations expressed that he was familiar with the Sirat via its presence in Arabic on the Internet. According to ‘SAM2’, production of the printed Sirat in 2016 averages 2,000 copies per month and is distributed to countries including Ethiopia and Pakistan.

3.6.8 Twenty-Seven and More Daughters from the Mother of the Books?

Another of the documents distributed by Jeff Hayes, but not written by him, refers to ‘JH’ as contributing to the Arabic of the Owen Sirat, and this would confirm what Hayes himself said above.[74] It also suggests that some Wycliffe translators had “interacted” with the Sirat, but that the work was largely that of Owen himself. In a cryptic phrase the same author said, “There was only one initial printing of Arabic Sirat. We picked up the rights from David Owen to translate Sira into non-Arab Muslim Languages. Altogether we counted 27 language translation projects underway and in various stages of completion. Unfortunately, David Owen withdrew permission.” Another correspondent used similar phraseology as he stated that the twenty-seven language projects would cover 95% of the non-Arabic speaking Muslim world. Since the publication of the Sirat Muslim Idiom Translations of the Bible, in whole or in part, have appeared in languages of Russia, Turkey, Indonesia and Iran, and they bear similarities in wording to the Sirat. The potential extent of the reach of the Sirat and its offspring is enormous.[75]

4. The Translational Influence of the Sirat

The data just examined suggests that at minimum the Sirat has influenced at least the following:

1. The True Meaning of the Gospel of Christ by Mazhar Mallouhi.

2. The Bangla and Urdu translations for Muslim audiences in Bangladesh and surrounding countries, the Oromo translation in Ethiopia, and usage—likely in Arabic—among the Fulani and Hausa in Nigeria.

3. Al Sabeel and Al Siraat in Lebanon, and the same in Israel/Palestine.

4. Audio versions of “The Lives/Stories of the Prophets” produced and distributed by Sabeel Media

5. Other projects kept under wraps. One example is the Al-Injil, which was published anonymously in 2012 and 2013.[76] Like Owen’s Sirat, it eviscerates Father and Son language, and it is a consciously Islamized translation.

Observations

This paper, with the tongue-in-cheek title ‘The Mother of the Books,’ uses qur’anic terminology to describe David Owen’s Sirat. Just as Islamic doctrine asserts an undefiled template of the Qur’an kept in heaven for the reproduction of subsequent qur’anic daughters on earth, so it would appear that the Sirat has spawned many offspring. Players like Mazhar Mallouhi, Jeff Hayes, Rick Brown, Larry Ciccarelli, as well as Milton Coke have served as mid-wives for the enterprise. Institutions such as Frontiers who significantly funded The True Meaning of the Gospel of Christ, denominational mission agencies, the Bible Society in Israel, Wycliffe/SIL with whom Brown and Ciccarelli were affiliated, as well as the Navigators with whom Jeff Hayes was affiliated, and Global Partners for Development who funded the printing of the Bangla MIT works, all have aided in the production of David Owen’s offspring. If one traces the distribution lines and major contributors to the Sirat back to their source, and then one might say that ‘all roads lead to’. . . America . . . and to a statistically significant number of players from the Fuller School of World Missions and Fuller Seminary. Here is a list of Fuller attendees or graduates who are/were involved in use, promotion, or translation of the Sirat and its derivatives:

- David Owen (1973-1976);

- Milton Coke (PhD, 1978);

- Mazhar Mallouhi (ca. 1974)[77] ;

- “SAM3” (MA, 1980);

- Belay Olam Guta (PhD, 2003);

- Dudley Woodberry (MDiv, 1960) dean and professor of Islamic Studies at the (Fuller) School of World Mission from 1985-1999. Greg Livingstone, former director of Frontiers, specifically mentions that he introduced Mallouhi to Charles Kraft and Dudley Woodberry at the Fuller School of World Missions.[78]

- Bob Blincoe the USA Director of Frontiers, who advocated for an Islamized Turkish translation, graduated with an MDiv and MTh (1974-1977) from Fuller.[79]

A Fuller graduate and former ministry colleague of Owen encapsulated the effect of Fuller on the Sirat when he said that it “is, and was, a faithful example of the ‘contextualization’ taught by Fuller Seminary in the 1970s.”[80]

5. Lessons For the Global Church

This case study illustrates that ideas have consequences, and the negative consequences for the global Church are obvious. Here is a list of lessons:

(1) A noble desire to reach Muslims with the Gospel can be derailed if its presuppositions are not carefully examined. Both Fairman in 1926 and Owen in 1987 stated the opinion that methods were faulty, and changing methods would cure the problem. This approach can be reductionistic; it fails to take into account the Biblical portrait of the unregenerate heart with the noetic effects of sin on the understanding, as well as the ideological antagonism of Islam to Christianity. Additionally, an overly-strong emphasis on receptor-focused communications can lead to a ‘whatever it takes’ pragmatic approach, and a consequent lack of respect for the Author of the Bible and the words He uses to communicate about Himself, such as Father and Son.

(2) Spiritual-sounding rationale for a Bible translation—e.g. “Spirit-led harvesters” —can mean very little if the philosophical underpinnings are faulty. For instance, the assumption that Islamic forms are neutral vessels into which one can pour Christian meaning is a recipe for danger, regardless of one’s declaration of being ‘Spirit-led.’ To equate God the Father in the Lord’s Prayer, as Owen did, with an Islamic-sounding ‘Lord of all the world’ is nothing less than an Islamizing of Christianity. As the Bible says, we are to “test the spirits” (I John 4:1).

(3) Conservative magazines such as Seedbed can be ‘used’ to advance an agenda which is not their own. Therefore, it is important that editorial staff members are vigilant and that they access informed resource people who can spot potential danger.

(4) Churches such as Blackstone Presbyterian Church can be introduced to a ministry vision that appears noble, revolutionary and game-changing all at once, but which is seen for what it is even by the Muslim apologist Ahmed Deedat. Therefore, it is important that churches ask hard questions about the philosophies behind the people and projects they support. Not only that, questions must be asked about actual field practice, as this can be more revealing than official policy documents. For this reason, the Biblical Missiology group developed a helpful standard of practice for missions.[81]

(5) Denominational mission agencies might have personnel and financial resources being used for ventures that they might not agree with if they knew exactly what was happening. Therefore, supervision of field personnel and awareness of their theological and philosophical leanings, along with financial expenditures, is incumbent on mission organizations.

(6) Scholarly-sounding phrases like “getting behind the text” and “avoiding crude anthropomorphic interpretations”—to quote David Owen—may appear erudite while masking other problems, the most important of which is the lack of belief in the divine inspiration of Scripture.

(7) The idea that “every group of people requires a special and individual presentation of the Good News in their own terms in order to facilitate effective communication” has a great deal of superficial appeal.[82] It was a bold step by the Pakistan Presbyterian Church to write a strongly-worded letter to a Bible translation organization stating that they no longer need ‘translations of convenience,’ which was a polite way of saying that they did not want Islamized translations.

(8) David Owen said, “Bible translators would have the initial, heavy responsibility of providing the terminology for such a movement that would allow it to integrate as yeast into the Islamic community.”[83] By linking his work with the term translation, in effect Owen has moved away from his ‘targum’ idea, to a translation. Therefore, one must be aware that the statement that a Muslim Idiom project is not technically a translation could constitute something more akin to plausible deniability in the face of the fact that the Scriptures are being distorted.

(9) The yeast that Owen talked about is spreading its infection in the world of Bible translation. Ideas by Eugene Nida on dynamic equivalence, and subsequent suggestions of dynamically-equivalent churches by Charles Kraft at Fuller, have resulted in some of the language of Owen’s Sirat. He describes Jesus as the MahdÄ«, who is a Muslim messianic end-time figure for Shi’ite Muslims, and describes a synagogue as a place of prostration or the masjid [=mosque].[84]

(10) It appears that advocates of the insider movement paradigm, including Kevin Higgins, Henk Prenger, David Owen, and the anonymous author corresponding with Jeff Hayes, all see MITs as a vital and important step for launching the subsequent movement of what they call ‘followers of Jesus within Islam,’ ‘Christian Muslims,’ ‘Messianic Muslims,’ ‘haraka Isawiyya’ or ‘completed Muslims.’[85] It is evident that they believe that Christianity is the fulfillment of Islam; an idea, which according to Adam Sparks, is theologically indefensible.[86] This is because equivalence is made between Messianic Muslims and Messianic Jews, or the fulfillment of the Old Testament in the New in Christ, and the fulfillment of Islam in Christianity.

(11) Although all of the above authors claim that they are making the Gospel more accessible to Muslims, what actually happens, as Mark Beaumont suggested, is that “what Jesus intended to teach is distorted and lost.” This has opened the door for the Islamic charge of corrupting the scripture [Ar. taḥrÄ«f] and deception. This actually makes the work of evangelizing by nationals even more difficult.

(12) The Islamization of the Biblical text is something that a former Muslim who is now ‘in Christ’ could easily spot. Yet it seems that Muslim Idiom Translation efforts consistently overlook this precious human resource. For these Christians from a Muslim background, the doctrine of their adoption as children of the heavenly Father is perhaps the most vital doctrine to their Christian walk, yet MITs would remove Father and Son language, as Owen did, without much thought. A Bible translation with fidelity to the Hebrew and Greek text, and to the collected wisdom of the global Church, according to these Christians, is much more useful in evangelism and discipleship efforts.

(13) The Medieval Islamic scholar ibn Taymiyya (d. 1328) saw the Gospels as nothing other than hadith-like stories about the life of Jesus. He saw them as a parallel to the “Lives of Muhammad” of his time. Ibn Taymiyya who railed against Christians and the church would more than welcome David Owen’s Sirat as nothing more than a life history of a man who exhibited prophetic tendencies.

(14) Under the umbrella of pragmatism, Owen spoke about using “Islamic style” but in reality, it morphed into Islamic thought forms and into a promotion of an Islamic worldview.[87] It appears that he has served the Islamic agenda more than a Christian one.

(15) On must ask if David Owen, like David Gray of SIL, justified his work as a “highly creative scripture use product.”[88] The data would suggest that there were no guardrails put in place for his out-of-the-box idea. A critical question is who should establish the guardrails? A para-church agency? A local church? The global Church? This author is convinced that the Bible is primarily a text addressed to the Triune God’s covenant people as he has endowed it to the global Church. It appears that it is her collective duty to ensure fidelity in all of its forms. This stance is different than much of the philosophy behind MITs which see the Bible or part of it as primarily an evangelistic tract whose language does not presuppose the exposition of Scripture on the part of church-trained personnel (Nehemiah 8:8).

(16) The premise that the skandalon (σκανδαλον) or offence to Muslims of the Father and Son in traditional Bibles must be removed or dulled-down somewhat to make the Bible acceptable is pervasive in the background thinking to the Sirat and MITs. The violent backlash by Muslims to the Sirat, however, demonstrates their level of acceptance.

(17) The dangers of lone-ranger translation efforts are obvious. The dangers of lone-ranger para-church organizations are obvious. The dangers of those who have a casual approach to ‘heresy’ and to become unhinged from “the culturally-bound confessions of Nicea and Chalcedon,” as Owen called them, are self-evident.

(18) In 1993, an eyewitness described David Owen as a ‘legendary figure.’ This raises questions about the discernment of his fellow colleagues.

(19) Money has aided in producing offspring from Owen’s project. One must ask where accountability to donors or supporting churches is or is not occurring. Did the denominational missionary who supported Owen have clear guidelines and accountability structures?

(20) The proliferation of Muslim Idiom Translations in Muslim-majority countries, mostly with the backing of Western funds, shows that this is more of a Western idea than one that nationals embrace. In fact, the history of Turkey, Pakistan and Bangladesh show that the majority of national Christians reject these ‘innovations.’ This fundamental lack of respect for Christian nationals is nothing less than a new colonialist, attitude which must be eradicated.

6. Conclusion

“Ideas have consequences.” The ideas that David Owen learned in his formative phase bore the fruit of his Sirat. Although it seemed to have met an untimely demise, a number of other individuals who had the same philosophical leanings as Owen had in his early days, resurrected the Sirat. These individuals, just as Owen, were helped by churches and organizations who gave wings to the enterprise and spread it from Bangladesh to Ethiopia, to Nigeria, to Lebanon, Pakistan and beyond. Is it not time that the Islamization program of these so-called ‘translations of convenience’ is exposed for what it is? Sadly, the likes of the Muslim apologist Ahmad Deedat and the Muslim World League see through these translations while less-than-discerning Christians continue to support their efforts.

Finally, the highest court of appeal in rejecting the usefulness of the Sirat is that it tarnishes the honor of the Triune God. It diminishes the honor due to God the Father in its version of the Lord’s Prayer. It reworks Simon Peter’s statement in all of its Christological glory, “Surely you are the Christ, the son of the living God” (Matt 16:17) to its sullied rendition, “Surely you are the living Word of Allah and his salvation made manifest.” It purports to help the all-powerful Holy Spirit who can turn hearts of stone into hearts of flesh, by ‘tweaking’ the Word of God so that no Muslim will be offended. The offence of the Sirat is against the Trinity.

References

[2] David Owen, “Project Sunrise Publication Report,” (Larnaca, Cyprus: np 1987), 5. The term ‘Muslim-friendly’ can encompass a range of translational approaches, from highly-Islamized works, like the Sirat, to Bible translations used in Muslim-majority areas which read more like an NIV or ESV than a KJV.

[4] By definition, a Muslim Idiom Translation (MIT) is one, which uses Islamic terminology, Islamic-sounding literary conventions, and Islamic thought patterns to render the meaning of the Bible in a manner more acceptable to the Muslim reader/listener. Andy Clark of SIL defined an MIT this way: “Translations contextualised for M people groups in a way which communicates best to them but often not to Western Christians or even traditional churches in the area, using e.g. … “Non-literal rendering of ‘Son of God.’” Andy Clark, “Exploring Muslim Idiom Translations,” PowerPoint Presentation IALPC (unpublished document, 2011): Slide #7.

The phrase ‘highly creative scripture use products’ comes from David Gray, “Translating for Contextualized Faith Communities,” (unpublished document, 2010): 8.

[5] Owen, “Project Sunrise Report,” 11-12. A person whose correspondence was noted by Jeff Hayes, who worked with David Owen, stated the following: “David was a Fuller student in the late 70s. He heard about contextualization and decided to attend mosque and acquire an insider understanding of Islam.” Anonymous, (unpublished document distributed by Jeff Hayes, 2004). In his “A Jesus Movement Within Islam,” under his initials D.O., David Owen talks about a sixteen-year “mission pilgrimage.” That would coincide with a beginning around 1975 when he was in attendance at Fuller Seminary. Interconnect 5 (1991): 12–27 [12]. Although this article was attributed only to ‘D.O.’ two independent sources have confirmed David Owen’s authorship. To date, Owen has not responded to this author for final verification.

[6] Charles Kraft, “Distinctive Religious Barriers to Outside Penetration,” in Media in Islamic Culture, C.R. Shumaker ed. (Clearwater, FL: International Christian Broadcasters and Wheaton, IL: Evangelical Literature Overseas 1974) and his “Dynamic Equivalence Churches in Muslim Society,” in The Gospel and Islam: A 1978 Compendium, Don M. McCurry ed., 114-128 (Monrovia, CA: MARC, 1979).

[8] This person will be referred to as ‘SAM3,’ and is a living person who has been in correspondence with the author.

[9] Owen, “Jesus Movement,” 23.

[10] Phil Parshall, New Paths in Muslim Evangelism: Evangelical Approaches to Contextualization (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1980). The official thesis title was “A Contextualized Approach to Muslim Evangelization.” Note the parallels between Henry Riggs’ 1941 article “Shall We Try Unbeaten Paths in Working for Moslems?” The Muslim World 31, no. 2 (April 1941):116–126; and that of Parshall and Owen’s work.

[14] Owen, “Project Sunrise Report,” 3, 11.

[15] Ibid, 21. Owen cites Kenneth Cragg’s opinion that the document was originally produced by Constance Padwick.

[16] Ibid, 3. David Owen also delineated his views on ‘staying inside of Islam’ in his “Jesus Movement,” 16. Note the parallels between this phrase and one spoken by Charles Kraft in 1974 “that we bend every effort towards stimulating a faith renewal movement within Islam” in his “Psychological Stress Factors among Muslims,” Media in Islamic Culture, 143.

[17] Ibid, 3, and repeated verbatim in his “Jesus Movement,” 27. In his “Jesus Movement,” (13-14) Owen suggests that the language of conversion should be erased from missionary vocabulary. This also manifested itself at the pro Insider Movement, Common Ground Consultation of 2009 in Atlanta, where it was almost one of the first items of the agenda.

[18] Owen, “Project Sunrise Report,”11. The ‘Hayes’ document also mentions “unofficial support” from the Bible Societies, but the extent is unknown.

[19] Both persons have asked to remain anonymous and hereafter will be referred to as ‘SAM1’ and ‘SAM4.’ ‘SAM4’ had already advocated using “Islamic thought forms” in outreach to Muslims in the 1970s. Over a period of time ‘SAM4’ observed Owen’s ministry. He described himself as a ‘friend and advisor’ and attested to Owen’s departure from the Christian faith. ‘SAM4’ telephone conversation with author, July 1, 2016.

[20] Owen, “Project Sunrise Report,” 7. Officially it was entitled Sirat-ul-Masih bi-lisan ‘arabi fasih [The Life of the Messiah in a Classical Arabic tongue] (Laranca, Cyprus: Izdihar Ltd., 1987). According to Owen, the Sirat used John Calvin Reid’s His Story: A Chronological Account of the Life of Jesus from Good News for Modern Man (Waco, TX: Word, 1973) as its inspiration. Another life of Christ for Muslim readers is Dennis E. Clark, The Life and Teaching of Jesus the Messiah [Sirat-ul-Masih, Isa, Ibn Maryam] (Elgin, IL: Dove Publications 1977). The Lord’s Prayer in Clark’s version, very much unlike Owen’s rendition reads, “Our Heavenly Father, may your name be honored…” (p. 53).

Whether he was aware of it or not, Owen’s Islamized Diatessaron already had a precedent from the Muslim scholar IbrÄhÄ«m al-BiqÄÊ¿Ä« (d. 1460). According to Walid Saleh, he had used the Torah and the four Gospels, but especially Matthew to produce the ‘first instance of an Islamic Diatessaron.” Walid Saleh and Kevin Casey, “An Islamic Diatessaron: Al-BiqÄËÄ«‘s Harmony of the Four Gospels,” Translating the Bible into Arabic: historical, text-critical, and literary aspects, Sara Binay and Stefan Leder eds., 85-116 (Beirut: Orient-Institut Beirut, 2012).

[21] In PDF form: http://www.jesus-for-all.net/islamic_books/pdf_0051.pdf or https://www.dropbox.com/s/5e48dppnu2xig5r/Owen%20Sirat%201987%20Arabic.pdf?dl=0

[22] https://www.dropbox.com/s/jeommjtkvhw8j15/Owen-Sirat%20comparative%20chart%20with%20NASB.doc?dl=0

[24] Ibid, 3. In his “Jesus Movements,” 18; he states, “The use of traditional ecclesiastical language, or even a neutral approach, WILL NOT support a Jesus movement [within Islam].” (Emphasis in original.)

He envisions that the believers within this movement will be called Muslimun lsawiyun (singular-Muslim lsawi) and that they would not have a problem reciting the shahada or Islamic confession of faith (p. 19).

It is important to note that in Islamic theology the genre of biography (Ar. SÄ«rat) is not viewed as divinely-inspired literature. Thus, the Owen Sirat could have the side effect of taking the content of the Gospels out of the realm of Biblical inspiration and consequently diminish its authority.

[25] An example of an Islamic life of Jesus as a prophet is Ibn ‘Asakir al-Dimashqi (d. 1176) Sirat Al-Sayyid Al–Masih. The naming of places such as Jerusalem or Galilee where the chapter was ‘revealed’ approximates Islamic occasions of revelation (Ar. asbÄb al-nuzÅ«l) or the circumstances in which a particular sura of the Qurʾan was sent down. Subtly, this can imply to the readers of the Sirat that Biblical inspiration and qurʾanic inspiration are roughly the same. Cf. Samuel Schlorff, Missiological Models in Ministry to Muslims (Upper Darby, PA: Middle East Resources, 2006), 45-46.

[26] David Owen, “Project Sunrise,” Seedbed 1, no. 4 (1986); David Owen, “Project Sunrise, Principles, Description and Terminology,” Seedbed 2 (1987); David Owen, “A Classification System for Styles of Arabic Bible Translations,” Seedbed 3, no. 1 (1988): 8-10. For reactions to it, see Samuel Schlorff, “Feedback on Project Sunrise (Sira): A Look at ‘Dynamic Equivalence’ in an Islamic Context,” Seedbed 2 (1987): 22-32.

[27] Issues 1-9 were published from 1989-1993. Daniel Johnson [pseud.], “Towards a Contextualized Ministry Among Muslims,” Melanesian Journal of Theology 20, no. 2 (2004), 50; repeats this article almost verbatim at many points. It includes a quote about ‘Spirit-led’ harvesters, similar to that of Owen. Owen’s article defends the philosophical basis for those Muslims who become believers in Jesus, somehow, to stay firmly embedded in their religion of Islam, their Islamic community and their Islamic practices. This is very much a seminal document for the Insider Movement, and not coincidentally, many of the players who endorsed Owen’s Sirat endorse the Insider Movement. Here again, Owen is not completely original, and again, his ‘grandfather’ Henry Riggs had suggested already in 1938 that “the ultimate hope of bringing Christ to the Moslems is to be attained by the development of groups of followers of Jesus who are active in making Him known to others while remaining loyally a part of the social and political groups to which they belong in Islam.” Henry H. Riggs, ed., Near East Christian Council Inquiry on the Evangelization of Moslems (Beirut: American Mission Press, 1938), 7.

[28] ‘M.B.’ [pseud.], “Qur’anic Style in Sirat ul-Masih,” Seedbed 4 (1990): np. [3rd out of 4 pages]. Also his “The Lord’s Prayer in Smith-Van Dyke and Sirat al-Masih,” Seedbed 5 (1990): 52-4. In his doctoral thesis Beaumont appears to be far less critical of the Sirat and justifies the removal of Father and Son under the rubric of “genuine dialogue.” Ivor Mark Beaumont, “Christology in dialogue with Muslims: a critical analysis of Christian presentations of Christ for Muslims from the ninth and twentieth centuries,” (PhD diss.: The Open University, 2002):249-50; 262. This thesis was reprinted as Ivor Mark Beaumont, Christology in Dialogue with Muslims: A Critical Analysis of Christian Presentations of Christ for Muslims from the Ninth and Twentieth Centuries (Bletchley: Paternoster, 2005).

[29] Owen, “Project Sunrise Report,” 2.

[30] For Brown’s assertion see Rick Brown, “Part I and II: Explaining the Biblical Term ‘Son (s) of God ‘in Muslim Contexts,” International Journal of Frontier Missions 22, no. 3 (Fall 2005): 91–96 and ibid. 22, no. 4 (Winter 2005):135–145. Brown’s arguments are repeated almost verbatim with an implicit defence of Muslim Idiom translation by Cynthia L. Miller-Naude and Jacobus A. Naude, “Ideology and translation strategy in Muslim-sensitive Bible translations,” Neo- testamentica 47, no. 1 (2013): 171–190.

[33] Note the similarities of these instances with those of a document distributed by Milton Coke entitled “The Path” or Siraat. The Word Document has these properties: Author- Milton Coke; Company-Global Partners for Development. Another earlier unedited version of 2005 lists the author as Jeff Hayes and the Company as Global Partners for Development. The implication of the hand of Jeff Hayes in both the Owen and Coke editions is very strong. Also see Adam Simnowitz’ article, “Nine Reasons Why I Named Jeff Hayes as the Main Translator and Responsible Party for Al-Injil,” (March 7/2016). Online: http://biblicalmissiology.org/2016/03/07/nine-reasons-why-i-named-jeff-hayes-as-the-main-translator-and-responsible-party-for-al-injil/

[34] The citation reads: (Atlanta: Global Publications). This appears to be the copyright holder somehow, yet Owen did withdraw permission to publish. Curiously, this publisher is based in Atlanta, Georgia with the name ‘Global,’ and Milton Coke’s ‘Global Partners for Development’ also uses the term ‘Global’ and is based in Tucker, Georgia.

[36] Personal correspondence from ‘D. H.’ to Rick Brown, commenting on Brown’s “‘Son of God” and “Son of Man”: Exegesis and Translation,” (unpublished document, February/March 2000).

[37] Sam Schlorff, “The Translational Model for Mission in Resistant Muslim Society: A Critique and an Alternative,” Missiology 28, no. 3 (Jl 2000), 311. Schlorff cites the Moroccan paper, al-‘Alam, April 2, 1989. Also, see his Missiological Methods, (2006), 46.

[38] Phil Parshall, “Lessons Learned in Contextualization,” in Muslims and Christians on the Emmaus Road, J. Dudley Woodberry ed. (Monrovia, CA: MARC, 1989), 264.

[39] Phil Parshall, “Approaches to Muslims,” Lecture Notes Columbia ICS, MIS 6071, July 25-29, 2011. Parshall is likely referring to Owen’s “Jesus Movement,” 23-24 where he suggests that creating a heretical group within Islam is better than them remaining non-Christians. Charles Kraft in personal correspondence to this author, remarks, “I observe that any new approach will probably include some heresy–albeit with a move towards orthodoxy as soon as possible.” Dated March 30, 2015.

[40] This is detailed in a circular prayer letter dated 9/8/01 [Names withheld]. The information was further corroborated by ‘SAM4’ in a July 1/2016 telephone call with the author.

[41] Sirat subsection “The Lily”: 7-10 with the English from the 1992 Arabic–English edition. It is noteworthy that Arabic versions of the Diatessaron retain ‘Father’ in the Lord’s Prayer, whereas Owen does not. See Hope Hogg, The Diatessaron of Tatian, 67. Online: http://www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu/03d/0112-0185,_Tatianus_Syriacus,_Diatesseron_[Schaff],_EN.pdf

[42] Owen, “Jesus Movement,” 18.

[43] The Arabic word for prayer, but in Islam it is the technical term for Islamic prayers.

[44] Literally: ‘O God.’ The holiness of God the Father is absent.

[45] Remembering Allah is one of the primary commands of Islam.

[48] AbÅ« Muḥammad al-QÄsim/ alt. al-QÄsim ibn IbrÄhÄ«m al-RassÄ«, Radd Ê¿alÄ l-Naá¹£ÄrÄ [A Retort to the Christians] as quoted and translated by David Thomas, “The Bible in Early Muslim Anti-Christian Polemic,” Islam and Muslim-Christian Relations 7 (1996): 36.

[52] Personal and private e-mail of March 2015. In an e-mail dated, September 8, 2015, David Harriman, detailed his involvement in the The True Meaning of the Gospel of Christ:

As Chief Development Officer for Frontiers, I was responsible for the fundraising effort that raised nearly $215,000 for the True Meaning of the Gospel of Christ, a new Arabic translation of the Gospels and Acts, with companion commentary, led by a Middle Eastern member of Frontiers [i.e. https://www.frontiersusa.org/]. Because the salient and distinguishing features of this translation — the removal of all instances of “Father” in relation to God, the selective removal of “Son” in relation to Jesus Christ, and the effective redefinition of “Son of God” by the insertion of qualifying, parenthetical statements within the text — were not disclosed to me, this information was withheld from the nearly 600 donors who funded this translation, and the thousands more who were solicited.

David Harriman, email message to Adam Simnowitz cited in his “Muslim Idiom Translation: Assessing So-Called Scripture Translation For Muslim Audiences With A Look Into Its Origins In Eugene A. Nida’s Theories Of Dynamic Equivalence And Cultural Anthropology,” RES 7972 Intercultural and Muslim Studies Integrative Seminar, Columbia International University, (2015): 11, n25.

[53] Rick Brown publicly advocated for the True Meaning as he said it uses “the true language of the readers rather than loanwords that are misunderstood and expressions that sound awkward and foreign” and that it “affirms the cultural identity of the audience while clearly communicating the biblical worldview.” In his “Muslim and Christian scholars collaborate on ground-breaking gospel translation and commentary,” Albawaba News, June 4, 2008. Online: http://www.albawaba.com/news/muslim-and-christian-scholars-collaborate-ground-breaking-gospel-translation-and-commentary Accessed 2015/11/24. Also, see the “English translation of preliminary notes for True Meaning” which are Ciccarelli’s from a larger document entitled “Final Order of Lighthouse March 2008” (unpublished document, 2008). ‘Lighthouse’ was a pseudonym for True Meaning.

[54] http://www.al-kalima.com/content/the-portfolio/scripture Accessed 2015/03/26.

[55] Ekram Lamie Hennawie and Emad Azmi Mikhail, “The Philosophy behind the Arabic Translation The True Meaning of the Gospel of the Messiah,” Evangelical Review of Theology 37, no. 4 (2013): 349-360.

[56] Paul-Gordon Chandler, Pilgrims of Christ on the Muslim Road Exploring a New Path Between Two Faiths (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Pub. Group, 2008), 158.

[57] See: http://hayestranslation.com

[58] Anonymous, “Sira to Sabiil History,” (distributed by Jeff Hayes, 2004), n.p. Elsewhere in this document Hayes essentially provides a definition for a Muslim Idiom Translation as he describes “The Injeel” which was planned for 2009 and on which he had major input. He says it meets four qualifications which are “Islamic in style, vocabulary, theology, and thinking.” Anonymous, “Sira to Sabiil History” in The Hayes Word document, which he distributed at the Common Ground Conference in Arizona in 2008 on CD and has the following properties: Microsoft Word 10.0 Company: The Navigators, 09/09/2004 7:11 PM, 15/02/2007 6:49 PM.

[59] SIL Consultative Group for Muslim Idiom Translation: SIL Internal Discussion Papers on MIT #1, “A Typology of Bible Translations for Muslim Audiences” rev. 2, (January 2011). This paper would be followed by five others, notably, #2, “The Relationship between Translation and Theology;” #5: “Options for translating the term ‘Son of God’”; #6: “The father-son relationship between God and believers.”

[60] Online: http://www.jibonerkotha.com/?lang=en Accessed 2015/03/23.

[62] See article by Emily Belz, “Inside Out,” WORLD Magazine May 7, 2011. http://www.worldmag.com/2011/04/inside_out

[63] George King and Tom McCormick, “Muslim Idiom Translations in Bangladesh,” Evangelical Review of Theology 37, no. 4 (2013): 335-348.

[64] J. Dudley Woodberry, “A Global Perspective on Muslims coming to Christ,” in From the Straight Path to the Narrow Way Journeys of Faith, David H. Greenlee ed. (Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity, 2006), 17. Earlier Woodberry also mentioned Owen’s Sirat along with other attractively packaged and contextualized Muslim-friendly works. He states: “Of special note is Arabic ‘Life of Christ’ (Sirat al Masih), based on a harmony of the Synoptic Gospels but using quranic idiom and style.” He adds, “for the most part, it has been well received by Muslims.” In his “Contextualization among Muslims: Reusing common pillars,” International Journal of Frontier Missions 13, no. 4 (1996):172.

[65] Darrell Whiteman, “Report on my trip to Bangladesh, October 6-11, 2007,” (unpublished document, 2007), n11. Whiteman links contextualization and ‘staying within Islam.’ The phrase “Jesus Movement within Islam” appears in a collection of essays edited by Whiteman and Gerald Anderson entitled, World Mission in the Wesleyan Spirit (Franklin, TN: Ashbury, Seedbed Publishing, 2014).

[66] An interview of Anwar Hossein and Bill Nikides on October 4, 2010 at Lynchburg, Virginia in “Interview of a former insider: Anwar Hossein,” in Chrislam: How Missionaries Are Promoting an Islamized Gospel, Joshua Lingel, Jeffery J. Morton, and Bill Nikides eds., 228-237 [235] (Garden Grove, CA: i2 Ministries, Inc, 2011).

[67] ‘SAM2’personal correspondence with author, October 8, 2015. ‘SAM2,’ is a pseudonym for a person instrumental in the propagation of the Sirat. He states that he hired a Bangladeshi national to produce the Sirat in Urdu.

[68] Belay Guta Olam, “Contextualizing the church among the Muslim Oromo,” (PhD, diss.: Fuller, 2003), 169.

[69] In his 1997 Master’s thesis at Fuller Seminary, Belay Guta Olam wrote, “I am also thankful to Milton Coke who guided me to Fuller Theological Seminary, School of World Mission.” In his vita, he states, “Belay joined Global Partners for Development in 1992 and served in Bangladesh as a missionary in Messianic Muslim Movement. He worked for Global Partners for two and half years.” In his “Muslim evangelism in Ethiopia,” (master’s thesis, Fuller, 1997), iv, 161.

[71] Online: http://issawiyoun.weebly.com; http://www.islameyat.com/post_details.php?id=701&cat=23&scat=31& Accessed 2015/11/21. PDF version: http://www.jesus-for-all.net/islamic_books/pdf_0051.pdf

[74] This Word document has the following properties “Microsoft Word 10.0 The Navigators 26/04/2004 8:03 PM 17/01/2006 1:10 AM.” The author refers to the Uzbek people as if he has first-hand knowledge of them, and goes on to say, “My own goal is to promote canonical Bible translation. We have found starting a Sirat al Masih translation project is a wonderful way forward.”

[76] Adam Simnowitz, “Jeff Hayes and Al-Injil: Another Mistranslation of the New Testament in Arabic Intended for “Insider Movements of Muslims” or C5 (C5/IM),” Biblical Missiology website (January 23, 2016). http://biblicalmissiology.org/2016/01/23/jeff-hayes-and-al-injil-another-mistranslation-of-the-new-testament-in-arabic-intended-for-insider-movements-of-muslims-or-c5-c5im/

In a subsequent article, Simnowitz provides nine reasons why he is convinced that the al-Injil comes from the hand of Jeff Hayes. “Nine Reasons Why I Named Jeff Hayes as the Main Translator and Responsible Party for Al-Injil,” Biblical Missiology website (March 7, 2016).

[77] Paul Gordon-Chandler, Pilgrims of Christ, 35; mentions that Mallouhi entered the School of World Mission at Fuller Seminary. From Chandler’s biography this would appear to be sometime after 1968 and before 1975.

[78] Greg Livingstone, You’ve Got Libya: A Life Serving the Muslim World. (Oxford: Monarch, 2014), 192.

[79] See: http://biblicalmissiology.org/2012/02/14/press-release-world-magazine-turks-pakistanis-and-bengalis-oppose-experimentation-with-bible-translation-by-western-mission-agencies/ ; also http://www.biblicalintegrity.org/2012/02/18/wycliffe-sil-translation-controversy/

Blincoe’s Linkedin profile states that he attended Fuller Theological Seminary between 1974-1977 and received a Masters in Theology.

[80] Forwarded email message to Adam Simnowitz dated, September 8, 2001. From his “Muslim Idiom Translation,” 67.

[84] Owen, ibid, 8-10 categorizes the theological terminology used in the Sirat. Beaumont notes that in every instance where ‘Son of Man’ is used in the canonical Gospels, Owen replaces it with al-MahdÄ«. For instance in his Sirat 25:48, he changes Matthew 25:31 to read: “the day is approaching; the hour of the MahdÄ«’s glorious return with row upon row of angels; then he will sit on his throne.” Beaumont, Christology in Dialogue with Muslims, (2005), 178-179.

[85] Kevin Higgins, “The Qur’an in Urdu as a resource for Bible translation in Muslim contexts: A case study in the translation of ‘spirit’ and ‘spirits’ in Urdu,” (PhD diss., Fuller Seminary, 2013); Henk Jan Prenger, “Muslim Insider Christ followers: Their theological and missional frames,” (DMiss diss., Biola, 2014).