On May 21, 1922, liberal pastor Harry Emerson Fosdick preached his famous “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” sermon. In commemorating its 100th anniversary, liberal Episcopal writer Diana Butler Bass conflates fundamentalism with American evangelicalism and Putinist Russian Orthodoxy as white ethnonationalism whose goals are dictatorially political and not so much theological.

Bass’ conflation is unfortunate not only because it is absurdly unfair but because the anniversary is important and merits serious reflection. American Protestantism’s division between liberals and conservatives more than 100 years ago has religious, political, and cultural implications for today.

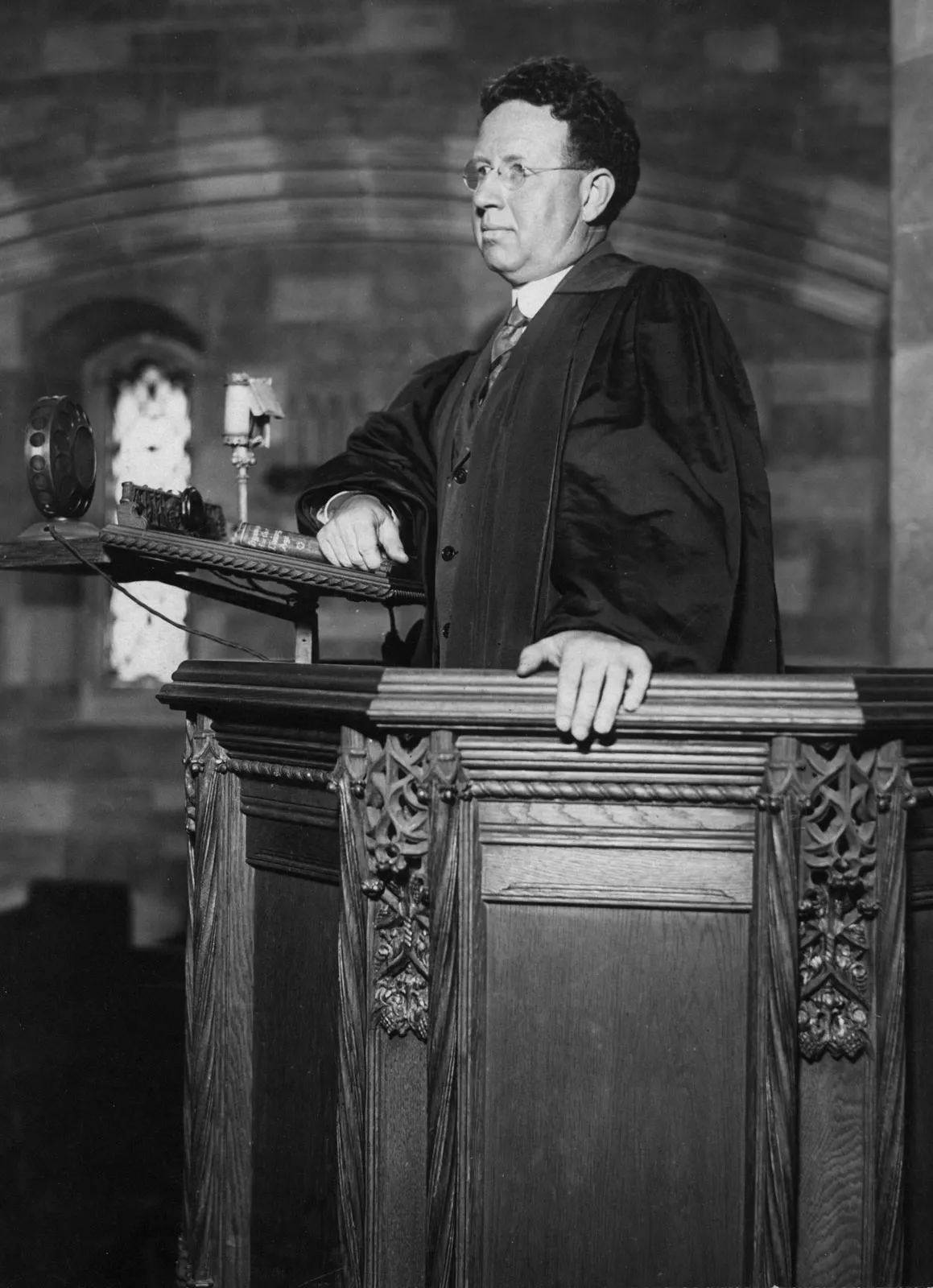

Fosdick was a modernist northern Baptist minister who, in the early 20th century, rejected Christianity’s supernaturality as irrelevant in the age of science and reason. Christ’s virgin birth, bodily resurrection, and atonement for human sins were antiquated concepts superseded by modern insights, Fosdick insisted. Instead, he believed contemporary Christianity should stress ethics and social reform. Fosdick’s anti-supernatural beliefs at that time were becoming entrenched in mainline Protestantism’s seminaries.

Although Fosdick was forced to leave a prominent pulpit in New York City, he was embraced by his patron, John D. Rockefeller Jr, a liberal Baptist who built for Fosdick the grand and Gothic Riverside Church in New York’s Morningside Heights, adjacent to Union Seminary, itself a flagship for Protestant modernism.

Fosdick’s 1922 sermon slammed fundamentalism as a sinister threat to progressive American Christianity. But theological progressivism had already largely won within mainline Protestantism. And by the 1920s, theological conservatives were largely banished from faculty posts in premier seminaries. Progressives assumed that fundamentalism and its insistent affirmation of Christian orthodoxy would eventually fade as modernity prevailed.

As Bass notes, that expectation was premature since fundamentalists, even while ostracized, constructed an alternative subculture that emerged with political power in the late 20th century. Butler claims Fosdick misconstrued fundamentalism as mainly a theological program when actually it seeks control and power.

Fundamentalists were always committed to the idea of America as a special place, blessed by God as an almost chosen nation and sort of a new Israel, Bass says. Although they loudly denounced America’s degeneracy, fundamentalists still saw the United States as God’s country, at least to the extent it upheld the morals and manners of “white America.” Fundamentalists want above all an orderly universe, she says, which informs their politics and cultural demands. And lots of fundamentalists do not believe in what Fosdick denounced. But, Bass argues, their political quest for control persists.

Authoritarianism and dictators in every culture do exploit traditional religion. And every religion can become tribalist, chauvinistic, and imperialist. But orthodox and creedal Christianity, in its affirmation of Biblical Christianity is the antidote, not the cause.

Bass does not leave her claims there. Provocatively, she asserts, “Political streams of American fundamentalism that have emerged in the latter part of the 20th century and early part of the 21st century have functionally merged with Russian Orthodox fundamentalism which is fighting an internal battle in global orthodoxy.”

Bass ties the “ethnonationalism” of U.S. white evangelicals with the “Russia world” perspective of Russian Orthodoxy under Vladimir Putin, which conflates the church with that regime’s geopolitical ambitions, most recently manifested in the invasion of Ukraine. “We are standing in the middle of Fosdick’s 100-year-old question,” Bass told an audience at Washington State University.

Neither Fosdick’s question nor the fundamentalists whom he targeted related to ethnonationalism and were, in fact, profoundly theological. He correctly identified the divide. Modernists rejected the supernatural. Traditionalists of all Christian traditions affirm it. Did Jesus bodily resurrect? Orthodox Protestants, Catholics, and Eastern Orthodox have always said yes. 20th-century liberal Protestants said no or were unsure.

Although Fosdick’s coreligionists were confident, they represented the future, all of the denominations that succumbed to their modernism have been in a nearly 60-year death spiral. Only churches that affirm the supernatural are growing, are racially diverse, and attract young people.

Bass partners U.S. evangelicalism with pro-Putin Russian Orthodoxy. But more relevant is the dramatic growth of the turbocharged supernatural-believing Global South Christianity that Fosdick never foresaw. Hundreds of millions in Africa, Asia, and Latin America pulsate to first-century apostolic Christianity with full belief in the supernatural, including the miracles of the Bible. They’ve no interest in Protestant modernism’s dry scientific moralism. This Global South Christianity is more democratizing than authoritarian.

Authoritarianism and dictators in every culture do exploit traditional religion. And every religion can become tribalist, chauvinistic, and imperialist. But orthodox and creedal Christianity, in its affirmation of Biblical Christianity is the antidote, not the cause. Christians who believe in a Savior born of a virgin and risen from the dead are more likely to resist demonic worldly ideologies than are adherents of a thin spiritual moralism.

Yes, the 100th anniversary of Fosdick’s “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” should be observed as an important milestone, but the collapse of liberal Protestantism comes as a warning of what happens when Biblical Christianity is denied. In contrast, we should reflect on the meaning of Christian faithfulness. Was the Son of God conceived by the Holy Spirit and born of a virgin? If so, let us follow Him.